The exhibition “Nothing. Just Leave!” Escape and New Beginnings in Buenos Aires, Montevideo and São Paulo focuses on three cities that have received little attention as destinations for German-Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany. Using the example of these three urban spaces, the difficult history of the decision to emigrate is traced through to the aftermath of this (family) biographical caesura in today’s South America. The quote that lends this exhibition its title – “Nothing. Just Leave!” – refers to the feelings of hopelessness and fear that many German-Jewish emigrants carried with them. It comes from an interview with Margarete Munk conducted by Corinna Below as part of the project “Ein Stück Deutschland” [A Piece of Germany] (https://einstueckdeutschland.com), in which the then 19-year-old Margarete Munk described her feelings on leaving the country. It provides the starting point from which the exhibition traces the emigrants’ various paths and decision processes. Personal testimonies such as photos and documents, interviews with contemporary witnesses, and newspaper articles, some of which are being presented to the public for the first time, shed light on individual decision-making and emigration paths, the challenges of arriving in an unfamiliar country, the new realities of life there and the complex relationship with the former homeland in the decades that followed.

A total of seven chapters present the similarities and differences between the

various emigration histories and destinations. While the chapters are arranged

vertically and trace emigration and its aftermath chronologically, the horizontal

level contains the stations that deepen the respective overarching theme in the

different urban spaces, illustrating it for each of the three cities presented.

Thus, in addition to the thematic access, there are also three geographical strands

that focus on Buenos Aires, Montevideo and São Paulo and add another structural

layer to the exhibition.

[More on structure and

function]

Such an extensive online exhibition would not have been possible without the support of various individuals and institutions. We would especially like to thank all supporters who have given us insights into their (hi)story, placed their trust in us and thus made personal objects and testimonies accessible for the exhibition. It is only through these individual life stories that the abstract topic of flight and its aftermath becomes tangible. We are also indebted to the numerous institutions in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Germany that have generously supported us with source material. Our collaboration with Corinna Below and her project “Ein Stück Deutschland” [A Piece of Germany] (https://einstueckdeutschland.com) has been both an inspiration and a source for us. Last but not least, we would like to thank the students of the University of Graz who worked on the chapter “Local Circumstances” discussing the emigrants’ new life in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, and São Paulo in the summer semester of 2022 and thus actively contributed to the exhibition.

This exhibition is dedicated to Jewish emigration to Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. While the issues that preoccupied people – from the organization of emigration and expectations of the new homeland to the realities of life there and the aftermath of this major biographical disruption – were similar, the local circumstances differed in each country. The exhibition therefore follows an approach of presenting the overarching themes and stages of emigration (outline of the chapters) as well as illustrating individual life paths and fates based on the three locations Buenos Aires in Argentina, São Paulo in Brazil and Montevideo in Uruguay.

At the beginning of each chapter, you can always choose to explore a theme, such as “local circumstances” or “legacies,” across all cities or you can choose to learn about only one specific city. The large chapter tiles at the beginning can thus be used as an entry point for each respective city: once in the city, you can click your way to the next slide using the arrow keys. On each slide you can see in which city / country you are so that you won’t “get lost.” And at the end of a thematic unit you can jump to the next thematic unit of the respective city (marked by the ship symbol). So discover the stories and traces of German-Jewish emigrants in Buenos Aires, Montevideo or São Paulo. Or view the entire exhibition to discover parallel developments and differences between the three metropolises. In order to do this, simply click through the tiles. It is possible to switch between the strands (thematically or geographically) at any time.

From the difficult decision to flee to arrival in a new homeland

Uprooting - The leaving behind of the previous life

Uprooting - The leaving behind of the previous life

Detlef Aberle was born in 1922 and lived with his parents and his younger sister Margot on Gryphiusstraße in Hamburg-Winterhude, where he attended the Lichtwark School and, from 1935, the Talmud Torah School. In a literary text entitled “Aufbau im Untergang” [Building amidst Decline], which Detlef Aberle wrote in German in 1988, he describes his school years in detail and also recalls the formative experiences during his religious education at the temple on Oberstraße in Hamburg-Harvestehude, where he received religious instruction and was trained as a chasan (precentor). The religious education he received in the temple was not only an important anchor point in an increasingly hostile environment, it also became an important pillar in Detlef Aberle’s future life. Due to the increasingly aggravating situation in social and economic terms, Detlef and Margot Aberle’s parents felt they needed to think about emigration possibilities and to undertake exploratory trips to various countries beginning in 1935.

The uncertain conditions abroad and restrictive emigration legislation in Nazi Germany did not make it an easy decision to emigrate. Finally, their father succeeded in obtaining an entry visa for Argentina due to his business contacts in South America. Detlef Aberle remembers the preparations before the family boarded the ship to Buenos Aires in the port of Hamburg in May 1938 as “feverish.” He remembers his otherwise thrifty father hastily making large purchases in the months before their planned departure for South America. He bought tailor-made suits and even a piano in order to turn monetary assets into removal goods, which – so he hoped – were to be shipped as freight to Argentina and form the basis for the family’s new life in an unknown foreign country. The Reich Flight Tax, the levies on relocation goods, and the low exemption limit for taking foreign currency with them while blocking domestic assets meant economic expropriation and impoverishment for emigrants. In the excerpt from the conversation with Detlef Aberle that took place in 2003 as part of the Workshop of Remembrance, he addresses the difficult economic conditions of emigration, especially for the middle class, for most of whom a new start in another country meant a loss of socioeconomic status.

“When antisemitism became ‘official’ in 1933, many parents felt that it was high time to teach their children the basic concepts of a faith they themselves no longer observed.”(Detlef Aberle)

[Read more...]

“Argentina was better, but it was not easy to get a visa; it was made difficult for Jewish immigrants to enter the country. It was the time of the Evian Conference, which had gained notoriety; no one showed much interest in welcoming persecuted people.”

Preparations – The difficult path to emigration

Preparations – The difficult path to emigrationHanna Grünwald, who was born Hanna Meyer on August 11, 1905 in Bockenheim an der Weinstraße, stayed temporarily in Hamburg in the late summer of 1938 to settle emigration matters. Her brother Ludwig was already living in Argentina at that time and was able to help Hanna, her husband Fritz and their two-year-old daughter Renate to immigrate by means of so-called llamadas (guarantees). Despite her brother’s llamada, obtaining the necessary exit papers in Germany proved difficult. Fritz Grünwald writes of several unsuccessful attempts at the Argentine consulate in Hamburg and pinned his hopes on the embassy in Berlin. Presumably, the difficulties experienced by Hanna Grünwald and her family were due to the worsening situation after the Evian Conference in July 1938, in the context of which several South American countries – including Argentina – severely restricted the immigration of Jews. A secret communication already issued on July 12, 1938 (Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto, Circular no. 11, Buenos Aires, July 12, 1938) stated that no more visas were to be issued to persons who were leaving their home country as “indeseable e expulsado” (“undesirable or expelled”). Immigration permits that had already been issued were then revoked, presumably this was also the case with Hanna Grünwald. A visa was finally issued in Hamburg on September 24, 1938 and the family managed to leave for Buenos Aires via Antwerp and Le Havre. In Argentina, they would be able to build a new life.

Departure for Argentina – Farewell in the port

Departure for Argentina – Farewell in the port

“I was just happy to emigrate. Overseas! And by ship! Sin pena y sin gloria as they say: without sorrow and without joy, I left. Nothing. Just leave!”

Along with Bremen, Hamburg was an important port for emigration to South America.

Only with the outbreak of the Second World War did private shipping largely come to

a standstill and emigration became more difficult or other routes had to be chosen.

For the shipping companies, emigration meant a lucrative business, but for their

passengers, the departure of the ship meant a deep caesura and an emotional

challenge. While Margarete Munk boarded the Cap Arcona in 1937 full of anticipation,

Ruth Deutsch remembers how difficult it was for her to board the ship in Hamburg on

April 13, 1939, heading for an uncertain future: “And I dragged myself as if I had

to go to the gallows”.

Margot Aberle, who emigrated with her parents and her brother Detlef Aberle when she

was 10 years old, describes the

finality of saying goodbye and the drama of leaving the port, which was an emotional

and traumatic experience for her parents.

[Read more: Vague ideas about the unknown destination Argentina.]

[Read more: Vague ideas about the unknown destination Argentina.]

Uprooting - Leaving one’s previous life behind

Uprooting - Leaving one’s previous life behind

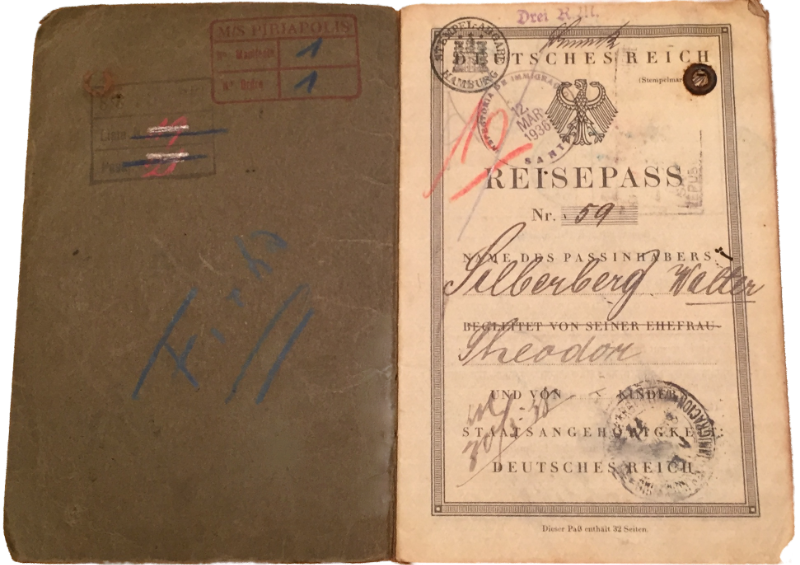

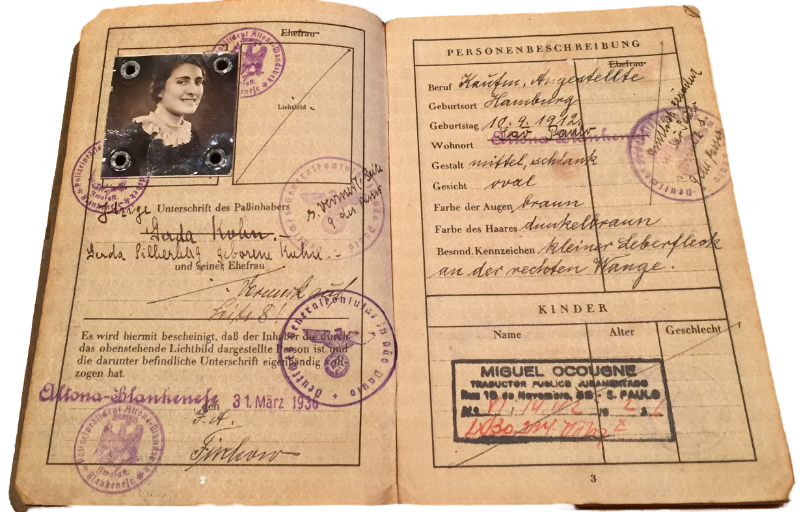

Making the decision to leave Hamburg, to go into exile and thus escape Nazi terror, was difficult for many German Jews. For them, it meant leaving behind their previous middle-class lives, abandoning their relatives and trusted friends (including their fellow sports club members, for example), vacating their well-kept apartments or houses, and coming face to face with the brutal reality of National Socialist Germany. At the beginning of Nazi rule, many were still hesitant to take this step and considered emigration into the unknown to be foolish and unnecessary – with hindsight, we know this was a complete misjudgment of the situation, of course. Some, on the other hand, saw emigration as a way out shortly after the National Socialist takeover. Beginning in 1933 an emigration movement set in that was primarily aimed at Germany’s neighboring countries or well-known destinations such as the United States or the British Mandate territory of Palestine. Brazil only slowly developed into an emigration destination, as information about the country was difficult to obtain and immigration regulations were restrictive. Nevertheless, Walter Silberberg emigrated to Brazil on February 21, 1936. His future wife Gerda Kohn was not able to obtain the required visa and to follow him to Brazil until September 1936. Gerda Kohn’s parents, who still hoped to avoid such uprooting, had a much more difficult time. It was not until January 10, 1939 that Emma Kohn fled to Brazil via the port of Hamburg. Her husband Arnold Kohn followed her on April 14th, 1939.

“On March 12, 1937, a few minutes after midnight, the steamer cast off. After the nervous tension of the last few days, I breathed a sigh of relief.”

Preparations - The difficult path to emigration

Preparations - The difficult path to emigration

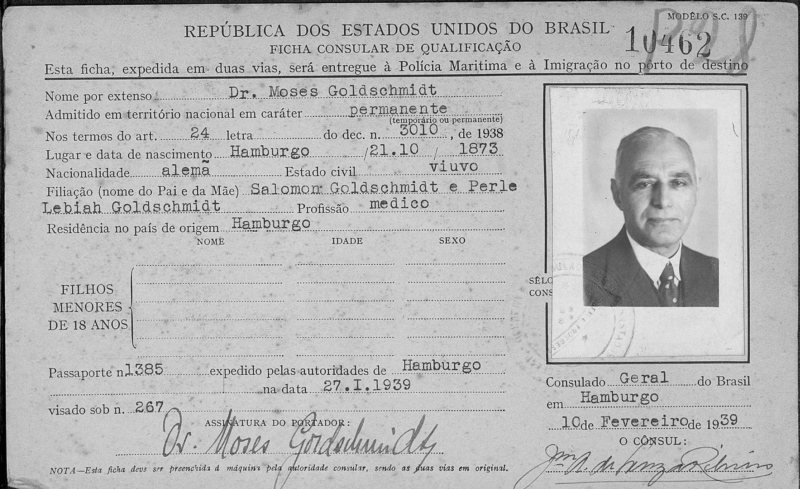

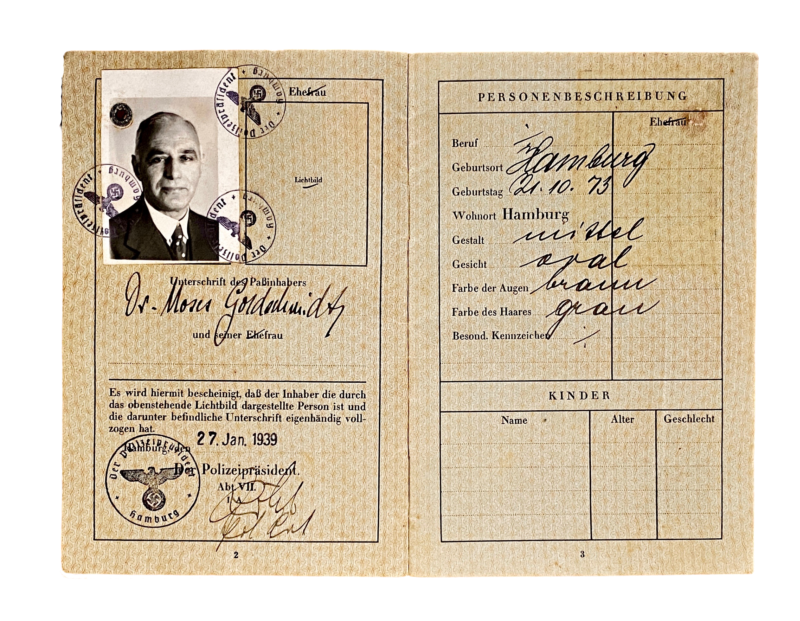

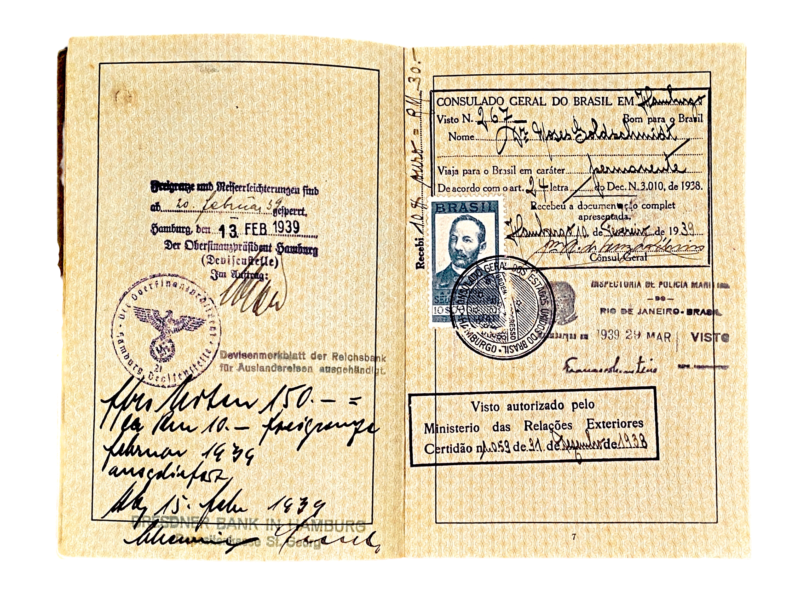

Facing increasing persecution in National Socialist Germany a growing number of German Jews decided to emigrate. Hamburg in particular developed into a central location for the emigrants, as many (general) consulates were located in the city. The Brazilian Consulate General also became a point of contact, as migrants could apply for the appropriate entry papers here. Since 1936, Aracy Moebius de Carvalho worked in the visa department there and helped German Jews obtain the necessary travel documents. Although Brazil had adopted a nationalist course under President Getúlio Vargas since 1937 and the government issued a secret letter to all diplomatic missions to prevent Jewish immigration in 1938, Aracy continued her assistance. When João Guimarães Rosa, Aracy's future husband, came to Hamburg in 1938 as vice-consul of the Brazilian mission, both intensified their assistance to Jewish refugees, which is why Aracy in particular was later given the nickname “Angel of Hamburg.” The Hamburg physician Dr. Moses Goldschmidt was among those who benefited from this support. He had already traveled to Uruguaiana / Brazil in 1937 to visit his sons Hans-Werner (emigrated in 1932) and Wolfgang (emigrated in 1934) and to attend a wedding. It was only after a tough interrogation by the Gestapo and additional compulsory payments that he had been permitted to take this trip. Yet he returned to National Socialist Germany and did not apply for an entry visa for Brazil until 1939, which he received at the Consulate General in Hamburg on February 10, 1939.

“The port of Hamburg, a hurried coming and going, a busy back and forth, a big farewell. – A ship is sailing out into the wide world. – Away from the people, who hurriedly exchange last words, last glances, a quiet woman sits in a corner of the big ship. [...] Once again they appear before her: the images of her husband, his grave, which she will no longer visit now, her city, her children, her friends, the years of her own youth and happiness.”

Departure for Brazil - Farewell in the port

Departure for Brazil - Farewell in the port

Leaving Germany was a challenge for many German Jews: while they continued to be considered German citizens, they had to endure significant harassment. The passports of Walter Silberberg and Gerda Kohn (later Silberberg) attest to the obstacles the Nazi regime placed in the way of the refugees. In addition to a German passport, those wishing to leave the country also needed a Brazilian visa. Furthermore, all assets had to be declared, the so-called Reich Flight Tax had to be paid, and a police deregistration form had to be provided. Due to the multitude of regulations, only some families succeeded in embarking on the journey into exile together, while others had to make their way alone. Walter Silberberg left Hamburg on February 21st, 1936, and reached Santos, the Brazilian port of immigration, on March 12, 1936. Gerda Kohn, who followed her future husband Walter into exile, also boarded the ship alone in Hamburg on September 1st, 1936 and reached Santos on September 26, 1936. The time on board the ship was surreal for many: filled with fear for the family members they had left behind, but also with hope for a new life, the ship became a place of being in-between. With the entry of the USA into the war in 1941 and the declaration of war by Brazil against the Axis powers in 1942, emigration by legal means became almost impossible. Due to the Brazilian entry into the war, the Consulate General in Hamburg closed and the Consul General as well as the embassy staff, e.g. Vice Consul João Guimarães Rosa and embassy staff member Aracy Moebius de Carvalho returned to Brazil, which put an end to direct assistance to Jewish refugees in Hamburg.

[Read more: Vague ideas about the unknown destination Brazil]

[Read more: Vague ideas about the unknown destination Brazil]

“Naturally, the choice fell on South America.”

Uprooting - Leaving behind one’s previous life

Uprooting - Leaving behind one’s previous life

Rudolf Heymann was born in Hamburg in 1925 and grew up in the Eppendorf district in a liberal, largely assimilated Jewish family. When his father, who traded in furs and other animal products, had his export and import permit revoked by the Nazi regime in early 1938, the family began planning to emigrate. Unlike the majority of those who emigrated to South America, his father had not only language skills, but also business contacts and a so-called “Argentine honorary passport” that allowed him to enter Argentina without a visa. However, Rudolf’s family decided to make a new start in Montevideo, Uruguay, where his father also had business connections. Arriving there was relatively easy because of his father’s local contacts, as Rudolf Heymann recalls in the interview he gave to the Workshop of Rerembrance [Werkstatt der Erinnerung] in 1995. Nevertheless, despite these important contacts, his parents did not succeed in gaining a long-term foothold in Uruguay and overcoming their uprootedness. Meanwhile, the Hammerschlag family was also preparing to emigrate to Uruguay. Margot Hammerschlag had recognized the extent of the threat posed by the National Socialists early on and made efforts to find a place of refuge for her family. In October 1938, she succeeded in organizing emigration to Uruguay for her husband Franz Hammerschlag and their son Gerd. She herself and her daughter Steffi (later Wittenberg) stayed behind in Hamburg for the time being to sell off the household. The group picture was taken during Steffi’s three-week stay in the Jewish Youth Recreation Home Wilhelminenhöhe in 1939 – around six months before she and her mother emigrated as well. It was a last attempt to maintain a daily routine in an increasingly threatening and precarious situation.

Preparations - The difficult path to emigration

Preparations - The difficult path to emigration

“The Consul General of Uruguay in Hamburg [...] was called Rivas, and this Consul Rivas saved all their lives, more than one hundred and fifty Jews in the famous Kristallnacht. That night, the Jews whom they could not take to the concentration camps and who had already presented themselves at least once at the consulate or at the embassy, went to the Uruguayan embassy and sought refuge there.”

Consulates and embassies played a central role in the emigration process: On the one hand, they were a point of contact for those who tried to escape Nazi terror. On the other hand, they were a regulatory authority that enforced the immigration regulations of the destination countries on the spot and through personal contact. The decisions of individual consulate employees often had far-reaching consequences. The scope of action that could be applied in this context and how the behavior of the individuals involved was evaluated depended on many factors. One case that is as well documented as it is complex is that of Alexander Katzenstein, a German local employee at the Uruguayan consulate general in Hamburg. Born in Hamburg in 1902 and of Jewish origin himself, he had been employed at the consulate since May 1938 and had also been in contact with local visa applicants due to the increase in applications since November 1938. He admitted to the Nazi authorities that he had also received sums of money in the process. In the summer of 1939, he was arrested for foreign currency offenses and embezzlement and had to serve a six-month prison sentence. After his release, he had to perform forced labor until he was deported to Theresienstadt in February 1945. The two charges against him were also cited by the in a letter to the Hamburg tax office (Rechtes Alsterufer branch) dated May 16, 1939, as reasons why Alexander Katzenstein was not to be issued a tax clearance certificate for the time being, a document he had presumably applied for in preparation for his own emigration. In the 1950s, Katzenstein attempted to obtain compensation for imprisonment, citing his own situation of persecution and hardship, which included his family’s failed attempt to emigrate to Uruguay.

Departure for Uruguay - Farewell in the port

Departure for Uruguay - Farewell in the port

Steffi Hammerschlag (later: Wittenberg) grew up in Hamburg-Harvestehude in a liberal Jewish family. After her father and brother had already emigrated in October 1938, the visas issued at the consulate for her mother and herself, who were to join the rest of her family after the household had been dissolved, were declared invalid by the Uruguayan government due to allegations of bribery made against the consul. To finance the new visas – the costs had risen significantly in the meantime – Franz Hammerschlag set up a private chocolate trade in the German-Jewish community in Montevideo. It was not until December 1939 that Margot and Steffi Hammerschlag succeeded in obtaining another exit permit via Antwerp to Montevideo for a period of one month. During the crossing, Steffi Hammerschlag, who was 13 years old at the time, jotted down in her notebook, which she had begun shortly after the onset of the Second World War, the poem “A Sea Journey.” Her verses provide a childlike view of the passengers traveling with her and at the same time surprise us with an ordinariness of what is described, suggesting, for instance, the (childish) boredom during such a ship voyage. In the interview she gave to the Workshop of Remembrance [Werkstatt der Erinnerung] together with her husband Kurt Wittenberg Steffi Wittenberg recalls the atmosphere as pleasant. Especially after leaving European waters, she recalls a feeling of release setting in.

[Read more: Vague ideas about the unknown destinations Uruguay]

[Read more: Vague ideas about the unknown destinations Uruguay]

Vague ideas about one’s destination and first experiences on arrival.

Imaginations – Argentina, an unknown country

Imaginations – Argentina, an unknown country

Since emigrants had little knowledge about their potential destination countries, the Aid Organization for Jews in Germany [Hilfsverein der Juden in Deutschland] published leaflets containing information for emigration. In 1939, the second edition of the brochure “Jewish Emigration to South America” appeared, which already referred to the tightening of entry regulations in the wake of the Evian Conference in July 1938. After a brief summary, the text on Argentina describes the country’s climate, population, social and cultural life, and – with particular detail – its economy. In addition to explaining social customs, the brochure served in particular to assess opportunities on the Argentine labor market, since there was a discrepancy between the commercial and academic professions of the German-Jewish immigrants and the labor needs in Argentina, which lay primarily in the agricultural sector. Occupational retraining courses were designed to facilitate integration and the building of a new existence in exile. In addition to these publications, the almost 300 counseling centers of the Aid Organization, including those in Hamburg, which organized, among other things, lecture evenings on emigration, served as sources of information the emigrants could use. The quote from Ilse Kramer, who emigrated to Argentina via the port of Hamburg in 1934, refers to (childish) hopes that could be associated with emigration – at least at the beginning of the 1930s: “On board the ship in Hamburg my mother said to me, “Oh, isn't it bad to leave like that?” And I said, “I’m going to be the rich aunt from America.”

Arrival – a sense of in-betweenness

Arrival – a sense of in-betweenness

Until the 1940s, a personal document – like the one for Albert Einstein shown here – was issued for each person entering the country. Afterwards, new arrivals could receive assistance at the so-called Hotel de Inmigración, which existed between 1911 and 1953. It offered immigrants free room and board for the first five days. In return, the new arrivals were expected to commit to finding a job with the help of the local placement office. In addition to dormitories with about 250 beds – in total, the hotel could accommodate 3,000 people – as well as dining and recreation rooms, the complex also included a bank for exchanging foreign currency, a post office for contacting family, and a hospital. Courses for vocational training or retraining were offered for men and women. The facility was thus both a support institution for the arrivals and an instrument of migration control. For the German-Jewish immigrants, a separate support network also developed, which also offered help in finding housing, catering for arrivals and support in finding work. The central organization was the Asociación Filantrópica Israelita, the aid association of German-speaking Jews. In 1985, the Museo de la Inmigración was founded in the Hotel de Inmigración complex, dedicated to the history of immigration. The importance of migration for Argentina is also reflected in the Día del Inmigrante (Immigrant Day), celebrated annually on September 4.

[Read more: Daily Life in Argentina]

[Read more: Daily Life in Argentina]

Imagination – Brazil, an unknown country

Imagination – Brazil, an unknown country

“Brazil is the future for those who part with their previous lives and are willing to work, even work hard, for all young and strong people. For those who are older and not strong, however, it is as everywhere in the world, if they do not have enough funds, it is very difficult.”

Only very few German Jews were familiar with Brazil as a country. Moses Goldschmidt, who had already traveled to Brazil in 1937 to attend his son’s wedding, thus belonged to a small minority within the refugee group who knew what awaited them. Others, however, had to glean knowledge about their place of refuge from newspaper articles, brochures or books, such as the one by Herbert Frankenstein. Eva Sopher (née Plaut), for example, reported, “We crossed the ocean without knowing what awaited us, without speaking the language of the country we had chosen. We really knew nothing about our new home. So it is not surprising that I assumed I would see monkeys on the street there.” The refugees’ perceptions remained vague, partly because the available books colored a rather clichéd picture. Herbert Frankenstein’s book, “Brazil as a Destination for Jewish Emigrants from Germany,” for example, touted the country's “healthy climate,” “economic boom” and “political stability” as reasons to immigrate. At the same time, the book exhorted all immigrants to observe the “three duties of the Jewish emigrant”: 1. not to endanger the “overall interests of Jewish emigration” through radical actions, 2. to seek integration into the Jewish communities and not to burden the social welfare system, and 3. to support the Aid Association of German Jews [Hilfsverein der deutschen Juden] through donations in order to enable others to emigrate as well.

Arrival – a sense of in-betweenness

Arrival – a sense of in-betweenness

“We emigrated only in 1939. With the second to last ship, so to speak. From Hamburg we sailed on the “Antonio del Fino”. When the war broke out we were on our way and they wanted to send us back. We were in Pernambuco, Brazil at the time. We were about 150 Jews on the ship. The German Jews of Brazil saved us. They negotiated with the shipping company somehow.”

Under the rising and increasingly violent pressure of persecution and exclusion in Nazi Germany, the question was no longer “Stay or go?” but “Where else can we emigrate to?.” When the Second World War broke out in 1939, it made migration even more difficult. Edith Nassau, who was on board the ship “Antonio del Fino” when the war broke out in 1939, was actually to be denied entry into Brazil because of her German citizenship. Through the intervention of the German-Jewish refugee communities in Brazil, Edith Nassau was nevertheless able to immigrate along with 149 other Jews. The shrinking possibilities for emigration often tore entire families apart. Letters remained the only means of communication for these families. Moses Goldschmidt, who had fled in 1939 to his two sons, Hans Werner and Gerhard Wolfgang in Brazil, wrote to his daughter Ellen in 1941: “You have to accept it with your head held high and make the best of it. Although it is excruciatingly painful for me to know that you are now so far away from me, I am happy to know that you [Ellen and her husband] have left Europe. [...]” While Moses Goldschmidt and his sons had sought refuge in Brazil, his daughter Ellen fled to Vichy France and India. They maintained contact by airmail letters, but this was significantly hampered and hindered by the long postal routes and censorship rules.

Imaginations – Uruguay, an unknown country

Imaginations – Uruguay, an unknown country

In December 1939, Steffi Hammerschlag (later: Wittenberg) left Germany at the age of 13 with her mother Margot Hammerschlag, following her father and brother to Montevideo. Although she too wondered what it would be like in the unfamiliar country of Uruguay, as a child she was guided primarily by her parents, she recalls in the 1995 interview. Knowledge about living conditions, the climate and society was thus low among the refugees. Yet the country was considered the "Switzerland of South America" and was also perceived by the arrivals - such as Steffi Hammerschlag - as European, which can be explained by the climate, architecture and sociopolitical condition of the country. Her uncertain expectations are illustrated by her various impressions of the ports the ship called at: while she was shocked by the backwardness in the Brazilian ports of Pernambuco and Recife, she was impressed by the metropolitan character in Rio de Janeiro. Montevideo immediately struck her as “pretty” and familiar because of its European flair. This positive assessment of the country was, of course, also related to the fact that arriving in Montevideo also meant being reunited with her family.

Arriving – a sense of in-betweenness

Arriving – a sense of in-betweenness

Arriving in Uruguay was easier for Rudolf Heymann’s family as well as for Margot and Steffi Hammerschlag than it was for other immigrants due to personal contacts in Uruguay and, in the case of the Heymanns, existing language skills. At the same time, Montevideo, as a “modern city,” as the brochure on emigration to South America reprinted in 1939 put it, offered a good infrastructure with “the most modern hospitals and schools,” in which “the whole level of life and culture” was on a par with “any large European city” . While the paperwork required for immigration was completed relatively quickly – Steffi Hammerschlag received a certificate of identity from the Uruguayan authorities as early as February, about a month after her arrival – economic integration was much more difficult for most immigrants.

Immigration politics

Immigration politics

Argentina advocated a largely liberal immigration policy until 1930, based on its 1853 constitution influenced by Juan Bautista Alberdi and his dictum “Gobernar es poblar” (“To govern is to populate”). The goal was to populate the fertile plains with Europeans, preferably from Spain and Italy, and to develop them agriculturally. In the course of the 1930s, the “safe haven” Argentina became an increasingly difficult escape destination due to anti-democratic domestic political developments and the military coup against President Hipólito Yrigoyen in 1930. From January 1, 1933 onward, immigration became possible only by “llamada,” i.e., by means of permission for family reunification or, for example, by means of an agricultural visa issued by the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA). While many of the Eastern European and Russian Jews who had immigrated in the 1910s settled in the agricultural colonies of the JCA, this was not an option for the Jewish refugees from National Socialist Germany or Central Europe since they had no prior agricultural training or education. Only 5% of the approximately 25,000 German-speaking Jews who emigrated to Argentina between 1933 and 1939 moved further inland after arriving in Buenos Aires. On July 12, 1938, Argentine Foreign Minister José Mariá Cantilo signed Circular 11, which instructed all diplomatic missions to stop issuing visas and passports to “undesirables.” Without using the word “Jews,” entry regulations were tightened significantly. Nevertheless, 40,000 to 45,000 Jews had been able to find protection in Argentina by 1945.

Society and Community

Society and Community

Many of the German-speaking Jews settled in the Belgrano neighborhood. The neighborhood became such a significant place that a special immigrant language, “Belgrano German” developed there. This is a mixture of German and Spanish, which reflects a divided reality of life for German-speaking Jews. However, the agglomeration in urban centers contradicted the “requirements of a healthy immigration policy,” as stated in the preamble of the Immigration Decree signed on July 28, 1938, which was connected to the Evian Conference and, at the international level, exempted Argentina from having to allow more immigration. Since industrialization could hardly take hold in Argentina due to the lack of iron and coal deposits, the production of agricultural goods and raw materials, such as beef, wheat or wool, remained the main industries. Accordingly, the demand for academics and merchants was low. In the future, only selected groups of people were allowed to immigrate who either had family contacts and sufficient means or who met the requirements of the labor market, such as technical specialists, contract colonists or theater troupes committed by contract to perform in Argentina.

In the Belgrano neighborhood, a distinct German-speaking Jewish milieu developed that allowed cultural and linguistic ties to continue to be maintained. The Pestalozzi School (Belgrano), for example, became cultural anchor point for many German-speaking Jews, who saw an important mission in passing on the German language.

[Read more: Realities of Life in Argentina]

[Read more: Realities of Life in Argentina]

“The model was that of Central European Jewry, more precisely in its organisation and mentality of German [handwritten added comment: "-speaking"] Jewry. ”

Brazil and Jewish immigration

Brazil and Jewish immigration

Brazil had a long history as a country of immigration - also for Jews. Already with the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492 and 1496, small groups of Sephardic Jews began to immigrate to Brazil. In the 19th century, mainly Jews came from Eastern Europe, i.e. from the Ashkenazic region. Also due to this immigration, small but lively Jewish communities developed in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. In São Paulo, Jews settled mainly in the districts of Bom Retiro and Mooca, with more Ashkenazi Jews settling in Bom Retiro and more Sephardic Jews in Mooca. A sign of the vitality of the Ashkenazi Jewish community is the modern Beth El Synagogue built in Bom Retiro in 1929.

The German-speaking Jews who were persecuted by the National Socialists and came to Brazil from 1933 onwards formed their own communities, for example in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Under Rabbi Fritz Pinkuss, the Congregação Israelita Paulista (CIP) was founded in São Paulo, which was supposed to offer a "home" as a unified community. A total of 13,975 Jews came to Brazil between 1931 and 1935, and another 10,600 between 1936 and 1939. Until Brazil entered the war in 1942, which destroyed all immigration possibilities, a total of about 25,000 Jews found refuge in Brazil.

Brazil - Immigration as a State Challenges

Brazil - Immigration as a State Challenges

The immigration of Jews to Brazil was determined by "utilitarian standards", which was mainly due to political changes in Brazil in the 1930s. These changes were initiated by Gétulio Vargas, who became president in 1930 and from 1937 established an authoritarian regime, the so-called Estado Novo, which pursued partly antisemitic, racist und anticommunist ideas.

Following European discourses, Jews were classified as a so-called non-assimilable race and officially discriminated against in the various immigration laws of the 1930s and 1940s, which set quotas for different groups. In addition, Circular 1.127 was sent to all Brazilian embassies and consulates in 1937 as a secret instruction to prevent the granting of visas and passports to Jews.

At the same time, the Brazilian state created exceptions in the immigration law and thus made it possible for special workers for agriculture, research and education at universities and in the arts to enter the country despite clear anti-Semitic restrictions. However, this immigration possibility remained reserved for only a small group.

[Read more: Realities of Life in Brazil]

[Read more: Realities of Life in Brazil]

Immigration Politics

Immigration Politics

As a sparsely populated country, Uruguay was eager to attract immigrants. Accordingly, Uruguayan immigration law was liberal and without severe restrictions. With the onset of the Great Depression of 1929, however, Uruguay tightened its immigration laws to protect its local labor force. Over the next few years, people seeking to immigrate were required to provide an increasing amount of supporting documents and had to meet specific criteria. For example, references about one’s ability to work, political activity, or health were required, and those over the age of 60 had to already have relatives in the country who could support them. Beginning in 1930, Uruguay underwent a political transformation. The newly elected president, Gabriel Terra, led the country into a dictatorship. Ideologically, he sympathized with the fascist regimes of Europe and was close to National Socialist Germany. However, the majority of the Uruguayan population rejected National Socialism. In 1938, the country returned to democracy under the new president Alfredo Baldomir. In foreign policy, Uruguay moved closer to the Allies, entering the Second World War on the side of the Allies in February of 1945. There was no tightening of immigration laws, as had happened previously under the Terra government.

Society and Community

Society and Community

Jewish immigration to Uruguay is documented from the beginning of the 20th century. For the period from 1933 to 1944, exact figures for Jewish migrants are hard to come by. A realistic estimate is that there were between 6,000 and 10,000 Jewish immigrants whose main destination was Montevideo. Many of the German-speaking Jews used the emigration route via Hamburg or Bremen. A large number of them also reached their destination via transit countries such as France or Italy. An important factor in favor of the otherwise rather unfamiliar Uruguay as a country of immigration was the fact that it remained one of the few countries still open to immigration. There was no official law that specifically excluded Jews from immigration, yet from 1938 onward Uruguay also required additional immigration documents, such as information about criminal records and political activity. An attempt to achieve an exclusion of Jews by means of a circular from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the Uruguayan embassies and consulates was unsuccessful. Despite warnings from right-wing conservatives that Jewish immigration would mean the local population would have to compete with these immigrants on the labor market, there was no further government regulation. A work permit was not required. So-called “entry jobs,” such as selling ice cream and flowers, often represented a first opportunity to earn money. Women often offered housekeeping services. Nevertheless, the first years often meant a professional and social decline for many German-speaking Jews. Those who were able to flee to Uruguay established a broad network of organizations and institutions such as a synagogue, political associations, recreational facilities and cultural initiatives. In 1936, members of the “Cultural Club of German-Speaking Workers” founded the Pestalozzi School in order to establish an alternative to the Nazi-aligned German School of Montevideo, which only existed until 1940. After 1945, many German-speaking Jews chose to emigrate to the U.S. and Israel because of family ties, economic prospects, and local political developments.

[Read more: Realities of Life in Uruguay]

[Read more: Realities of Life in Uruguay]

New beginnings between fear, hope and longing.

A difficult start – Challenges of a New Beginning

A difficult start – Challenges of a New Beginning

The Pestalozzi Society was founded in 1934 by the editor of the newspaper Argentinisches Tageblatt, Ernesto Alemann. He had Swiss roots and took an active stand against National Socialism, which led to his doctorate being revoked by Heidelberg University in 1936 due to his political activities. Alemann’s goal, in response to the growing influence of National Socialism in the German-speaking community of Buenos Aires and in conscious political opposition to it, was to found a school that would be a place for those fleeing the Nazi regime and that would be committed to humanist and democratic traditions. In 1938 the school was able to move into its new building. In order to strengthen the position of the school against its critics, its leaders (successfully) tried to win support from renowned German-speaking intellectuals: In various letters of congratulation from famous personalities to the school, for example from Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, Sigmund Freud or Stefan Zweig – the latter even visited the Pestalozzi School – the importance of the school was emphasized beyond the emigrant circles of Argentina, and its establishment was seen as an important sign. For the German-Jewish emigrant children, such as Margot Aberle Strauss, the school became a central place in their new lives, they met people with similar experiences here, could communicate in a familiar language and at the same time learned that of their new homeland.

“How quickly one forgot in the land of blue skies that basic melody of one’s school days, the building-amidst-decline feeling. Here there was no going through the cold.”

Connection – between old and new home

Connection – between old and new home

In April 1937, Anna Hess, who was 82 years old at the time, wrote the first letter to her daughter Martha (“Muckchen”) Meyer, who had emigrated with her family from Hamburg to Buenos Aires. For about six years, mother and daughter corresponded with each other about their daily lives. While Martha Meyer succeeded in building a new life in Argentina, her mother’s daily life was marked by increasing restrictions and disenfranchisement. Her daughter’s messages gave Anna Hess vitality, and writing and sending letters provided her with a structure: shipping schedules were studied and reply letters coordinated with them so that postal routes were as short as possible. The daughter let her mother share in her new life through detailed descriptions, thus opening up a world outside her own horizon of experience, which provided a brief escape from her own increasingly depressing everyday life in National Socialist Germany. Anna Hess’s last lines, in which she announced her “great long-planned journey,” meaning her imminent deportation to Theresienstadt, on June 8, 1943, did not reach her daughter in Buenos Aires until 1946, by which time Anna Hess had already been dead for three years. Her mother’s letters were kept within the family in Argentina until the great-granddaughter Madelaine Linden published them in 2017. ( More Information: https://www.swr.de/swr2/leben-und-gesellschaft/die-briefe-der-juedin-anna-hess-100.html and Madelaine Linden, Anna Hess. Briefe einer jüdischen Hamburgerin an ihre Tochter in Buenos Aires von 1937 bis 1943, 2017.)

“The great majority can lead a very modest bourgeois existence or is already proletarianized”(Quarterly Report July to September 1939, in Filantropía, 6)

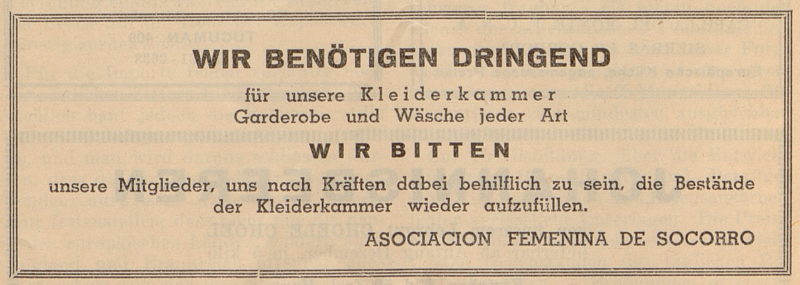

Solidarity – Networks in Buenos Aires

Solidarity – Networks in Buenos Aires

For most families, the new reality of life included a loss of socioeconomic status. In order to counteract the economic hardships and to ease the arrival in an unfamiliar country, an extensive network of support services developed among the German-Jewish newcomers, headed by the aid Asociación Filántropica Israelita. Its newsletter, “Filantropía,” reported on aid activities, called for donations, placed advertisements by small businesses, and also reported on the political situation in Germany or on emigrant communities in other countries. The services offered by the aid organization covered not only different areas such as social welfare, education or culture, but also different target and age groups. Thus, a women’s association was established as well as a children’s home and a retirement home. In addition to facilities for everyday needs, such as a sewing room or a clothing store, there were also offers for further education and entertainment, such as a reading circle or Spanish language courses.

A difficult start – Challenges of a New Beginning

A difficult start – Challenges of a New Beginning

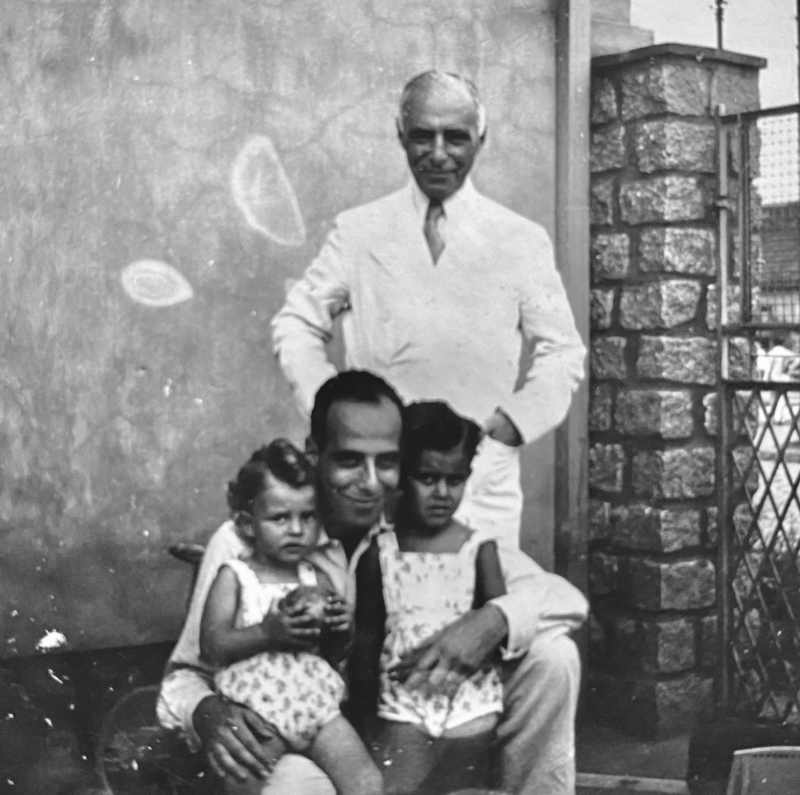

For many German Jews who went into exile, family became an important anchor. Walter Silberberg and Gerda Kohn, for example, were married in São Paulo in the same year they fled to Brazil (September 28, 1936). German Jews who had fled the Nazi regime often married other German-Jewish refugees, as the common German language and culture and the shared experiences of flight and expulsion created a deep bond that helped them to overcome the contemporary challenges of exile. Yet they could not completely retreat into the private sphere and family life since refugees were continuously confronted with political realities.

Yet they could not completely retreat into the private sphere and family life since refugees were continuously confronted with political realities. In addition, questions about their own citizenship and belonging had to be answered repeatedly. Gerda Silberberg (née Kohn) had her marriage recognized and entered in her passport at the German Consulate General in São Paulo as late as October 1936, as she understood this to be a requirement for a German citizen. However, the extent to which her identity as German citizen was questioned by the German authorities is illustrated by the entry of February 6, 1939. A note from the German Consulate General in São Paulo stipulated that Gerda Silberberg must now also use the first name “Sarah,” which shows that even in Brazil the defamatory and antisemitic legislation of Nazi Germany was being implemented.

“...who knows when this war will be over, whether with my failing health and advanced age I will even live to see the end. [...]”

Connection – between old and new home

Connection – between old and new home

Many German Jews were preoccupied with processing what they had experienced and living with the uncertainty about those who had stayed behind or their family members who had found refuge in other countries. In a letter dated September 16, 1941, Moses Goldschmidt describes the pain and the “sleepless nights” that the separation from his daughter (who escaped to India) caused him. He was also clearly troubled by his difficult financial situation. Facing such challenges, meeting and forming friendships with other German-Jewish refugees became important. It was not only the exchange and the building of new social networks, but also the shared memories and traditions of the “old homeland” that helped him cope, as Moses Goldschmidt described it in a letter dated October 12, 1941. “For coffee the other day we had a strawberry tart, the base was first-class shortcake and a coffee cake – a real taste of home.” In the same letter he also reported, “Even the cold supper was not half bad. I could even play skat now if I felt like it.” In contrast to these positive experiences, the harsh realities kept catching up with many refugees. In 1943, Moses Goldschmidt wrote to his daughter, “...how happy I would be if one day I could welcome you in the port of Porto Alegre or Rio. But I don't want to build castles in the air.” Besides the hope of a reunion, there was one thing that Moses Goldschmidt and many other German-Jewish emigrants considered important: “...to live long enough to see the Nazis punished.”

Solidarity – Networks in São Paulo

Solidarity – Networks in São Paulo

As Brazil’s economic metropolis, the city of São Paulo offered many German-Jewish refugees opportunities to build a new life for themselves. Some were able to use their professional qualifications from Germany and build on them. Others, however, had to find new fields of occupation, which was a particular challenge for many. Probably for this reason, a German-Jewish network developed in the city, which supported the refugees not only on a professional level. As early as 1933, Dr. Ludwig (Luís) Lorch, supported by his wife Luiza (née Klabin), founded the Comissão de Assistência aos Refugiados da Alemanha (CARIA), which assisted many refugees. Lorch also created the framework for the founding of the Sociedade Israelita Paulista (SIP, 1934) as well as the Congregação Israelita Paulista (CIP, 1936/37), a Jewish congregation that became the center of German Jewish refugee life. Among the founders were Dr. Hans Hamburger, former judge at the Supreme Court in Berlin (immigrated 1936), Dr. Alfred Hirschberg, former functionary of the Centralverein and editor of its newspaper (immigrated 1940), Fritz (Frederico) Zausmer, Wilhelm (Guilherme) Krausz (immigrated 1925) and the Rabbi Dr. Fritz Pinkuss (immigrated 1936). This German-Jewish network in São Paulo rendered the Brazilian metropolis particularly attractive for many Jewish refugees, as it facilitated a new start and the building of a new life without forgetting one’s roots.

A difficult start – Challenges of a New Beginning

A difficult start – Challenges of a New Beginning

In addition to the feelings of safety and freedom, the arrival in the new country of Uruguay also brought worries about one’s economic existence. For most of the German-Jewish families, especially those who, like the Hammerschlags, had led a middle-class life, emigration meant an economic decline. The lack of language skills and a professional background that in many cases did not meet local needs made finding a job difficult. Steffi Hammerschlag (later: Wittenberg) recalls in the interview she gave to the Workshop of Remembrance [Werkstatt der Erinnerung] together with her husband Kurt Wittenberg in 1995 that these “limitations” were felt from the beginning. Even for the children, for whom integration was often easier overall, the lack of language skills posed a challenge in everyday life. Steffi Hammerschlag, for example, had to attend school lessons in the early days without understanding a single word. At the same time, the resulting contacts and the forced rapid learning of the Spanish language helped her to find her way in the new environment. Steffi Hammerschlag also attended the Jewish sports club Maccabi, where she met other German-Jewish emigrants.

“For us, it’s different. We did not carry our bundle on our shoulders when we landed, we carried a heavy burden inside us. Instead of homesickness, we brought with us the woes of the homeland, which was a whole continent, which we crossed while on the run, escaped, chased, let off the ship after many formalities, which steered into port like an intruder.”

Connection – between old and new home

Connection – between old and new home

Even after they had been saved by emigration, German-Jewish refugees continued to follow the situation in Nazi Germany closely. In addition to their concern for family members and friends, some of them engaged with the concrete political struggle for another Germany, which would make a return to the former homeland possible. Rudolf Heymann, for example, a member of the resistance group “Das andere Deutschland” [The other Germany], became part of the political, German-speaking community of exiles in which the two anti-fascist groups “Das andere Deutschland” and “Freies Deutschland” [Free Germany] competed with each other. They debated the political order of a Germany to be rebuilt after the war. Rudolf Heymann also saw in the discussions an expression of the Europe-centeredness of the emigrants, a majority of whom continued to feel German. Kurt Wittenberg, Steffi Hammerschlag’s future husband, became involved with the German Anti-Fascist Committee of Free Germany in Montevideo and served as its secretary from 1943. As such, he participated in demonstrations and co-authored appeals such as the one on the occasion of the capture of Berlin on May 2nd, 1945, which read: “The Free Germans living in the hospitable Republic of Uruguay are ready to return to our homeland, liberated by the Allies, to free every last corner of Germany from the brown plague.”

Solidarity - Networks in Montevideo

Solidarity - Networks in Montevideo

In 1946, the board of the Nueva Congregación Israelita de Montevideo (New Jewish Congregation of Montevideo) could look back on ten years of congregational work and herald a phase of consolidation. The congregation was founded ten years earlier on June 6, 1936, as the Montevideo Synagogue Congregation, initiated by 14 immigrants from Germany. The founding of this congregation was initially strongly influenced by the idea of supporting new immigrants, which is illustrated by the fact that its first chairman, Mauricio Speyer, also headed the aid association Asociación Filantrópica Israelita del Uruguay. In the coming years, the congregation experienced a rapid growth in membership, due in part to the increasing number of immigrants: While in 1937 there were 167 members, by 1946 there were 4,500. At that time, the congregation maintained a community center, two synagogues (Maldonado and San Salvador), a religious school, a funeral society, a cultural commission, and the weekly community newspaper (Boletín Informativo), which began publishing in 1941 and from which the pages presented here are taken. In 1940 the congregation was officially recognized by the Uruguayan state. This was supplemented by existing social infrastructures of the other Jewish congregations, such as homes for the elderly and for orphans, as well as by a network of support services and associations, such as the Women’s League, the Zionist Union, and sports clubs.

Emigration as a (family) biographical caesura and the search for belonging.

“Not that we assimilated quickly. It was not only the foreign language that bothered us, but also the very different way of life of the celestes. We were used to living life within our own four walls. After all, it was cold out in the streets in more than one sense. Here, on the other hand, even business was conducted in the coffee house, and one could be sure that a person known for only a few minutes seriously claimed to be a friend and could hardly hide his laughter when one said goodbye stiffly, with a firm handshake, perhaps with a slight hint of clicking his heels together. We emigrants still stuck close to each other for a long time, and on Saturday afternoons social life took place nicely well-behaved at home.”

Belonging? Forming a community

Belonging? Forming a community

In his literary text written in 1988, Detlef Aberle describes not only his school years in Hamburg but also life in Buenos Aires, where his family had emigrated in May 1938. After the oppressive mood caused by the progressively worsening political situation in Nazi Germany, Aberle sketches in this passage an attitude toward life in his new homeland Argentina that is characterized by lightness and sociability. While as a 16-year-old boy he was open-minded and curious about this newness, the passage also illustrates the fear of contact with the Argentine environment on the part of many German-Jewish immigrants. The lack of language skills and the cultural differences, especially in the early days, led many to move primarily within their own community. Thus, their own networks, associations and places where they met and exchanged ideas emerged – such as the Aid Association [Hilfsverein] or the Pestalozzi School. Many of the German-Jewish immigrants lived in the Barrio Belgrano, where they visited each other and held on to cultural, linguistic or culinary traditions of the old homeland. Detlef Aberle, for example, found a new home in the liberal synagogue Bnei Tikvá, which he attended regularly until shortly before his death and on whose board he served. Not only rituals and architecture, but also furnishings and religious objects often created a bridge to the former homeland in the synagogues. In general, the practice of Liberal Judaism is a legacy of German-speaking Jewish immigration; in addition to lived practices, it was rabbis such as Wilhelm (Guillermo) Schlesinger and other graduates of the Jewish Theological Seminary in Breslau who established this tradition of Judaism in Argentina.

Identifying as German-Jewish-Argentinean?

Identifying as German-Jewish-Argentinean?

Even though Detlef Aberle describes himself as an “Argentinean” in this short interview excerpt, it is clear that the German language and culture remained an intellectual home for him throughout his life, which is expressed not least in the fact that he wrote his literary essay “Aufbau im Untergang” [Building Amidst Decline] in German. However, Detlef Aberle was not unique in cultivating the German language, German-Jewish circles generally did the same. The fact that many children were sent to the Pestalozzi School was based not least on the desire to pass on the German language to one’s children. In the following decades and the younger generations, this tendency has decreased, so that formerly rather self-contained institutions have merged into the larger Jewish communities.

[Read More: Getting in touch with the old homeland in Argentina]

[Read More: Getting in touch with the old homeland in Argentina]

Belonging? The CIP as a new home

Belonging? The CIP as a new home

The Congregação Israelita Paulista (CIP) in particular developed into a German-Jewish center or rather a German-speaking Jewish center in the city, as it brought together not only Jewish refugees from Germany but also Austria. The Jewish congregation adhered to the principle of a unified congregation, i.e. it promoted uniting all forms of Judaism under its roof. Apart from a small, conservative group, the majority followed the reform-oriented tradition, which had its roots in German Reform Judaism. Rabbi Dr. Fritz Pinkuss, who immigrated in 1936, became an important religious leader for the congregation and the CIP in this regard, making the Etz Chaim synagogue, which was rededicated in 1957, a center of Jewish life in the city. The German-Jewish families, such as the Silberberg family, felt a close connection to the synagogue and congregation, as the wedding pictures of Claudio Silberberg, the son of Walter and Gerda Silberberg, illustrate. The extent to which this congregation carried on the traditions of German Jewry is evident not only in the religious traditions, but also in the social activities, youth work and social welfare that the congregation organized. Similar German-Jewish congregations were established in Rio de Janeiro (Associação Religiosa Israelita, ARI, 1942) under Rabbi Dr. Heinrich Lemle and in Porto Alegre (Sociedade Israelita Brasileira de Cultura e Beneficência - SIBRA), which were in close contact with one another.

Identifying as German-Jewish-Brazilian?

Identifying as German-Jewish-Brazilian?

“I have been given refuge in this country, I was accepted in this country, so I belong here. Brazil is my home.“ (Eva Sopher, 1955)

After the end of the Second World War, most of the German Jews who had fled remained in Brazil, seeing the country not as a transit station but as their “new home.” Some of the German-Jewish refugees had difficulties integrating into Brazilian society, but the majority quickly acculturated and managed their own economic consolidation. The many clubs and institutions that German Jews founded or joined in São Paulo also helped. The Club A Hebraica, inaugurated in 1957, advanced to become one such important association (today it has about 33,000 members). In addition, the Jewish congregations registered a lively growth, so that in 1966 there were about 125,000 Jews living in Brazil out of a total population of 85 million. 50,000 of these lived in Rio de Janeiro, 45,000 in São Paulo, 12,000 in Porto Alegre, 3,000 in Recife, and 2,000 each in Bahia, Belo Horizonte, and Curitiba. Many of the German-Jewish refugees became Brazilian Jews in the following decades, but they preserved the religious-cultural traditions and sometimes even passed on the German language to the next generation. In addition to coming to terms with their own German-Jewish past, as Brazilian citizens they now also had to face the present circumstances in their new homeland. In 1964, the military staged a coup in Brazil and established a military dictatorship that was to last until 1985 and initially aroused fear among the former refugees in particular.

[Read More: Getting in touch with the old homeland in Brazil]

[Read More: Getting in touch with the old homeland in Brazil]

Belonging? Forming a community

Belonging? Forming a community

Approximately 9,000 German Jews immigrated to Uruguay, also called the “Switzerland of South America,” between 1933 and 1945. In addition, there was a larger group of Eastern European Jews as well as those of Sephardic origin. In 1934, an aid association of German-speaking Jews was founded, which took care of the increasing number of immigrating Jews, for example with accommodation, food, cultural offers or support in finding work. Religious life was organized according to nationality. In his 1995 interview with the Workshop of Remembrance [Werkstatt der Erinnerung], Rudolf Heymann recalls that “the community center [...] was the actual refuge for the vast majority of these immigrants, where they found their kind.” The German-language radio program “La Voz del Día / Die Stimme des Tages,” which Hermann P. Gebhardt had launched in 1938 as a “spoken newspaper” and “anti-Nazi broadcast,” informed listeners about domestic and foreign policy as well as sports and culture. For many, tuning in every day was a firm ritual.

Identifying as German-Jewish-Uruguayan?

Identifying as German-Jewish-Uruguayan?

After Rudolf Heymann had become involved in the Zionist movement in Montevideo and had been involved, among other things, in the founding of the youth group Hashomer Hazair, he emigrated to the newly founded state of Israel in 1949. He himself saw the turn to Zionism as a reaction to the disappointment that there had been no revolt against National Socialism in Germany – a hope he had shared with the other members of the left-wing socialist resistance group “The Other Germany” in Uruguay. At the end of the 1950s, Rudolf Heymann was sent as a delegate to Berlin, tasked with establishing a Zionist youth movement in West Germany. He had previously turned down an offer to do this work in South America because he had always felt a foreigner there. In Berlin, on the other hand, he had quickly felt “at home” under the “cloak of the Zionist agent.” The family then moved to Hamburg, Heymann’s birthplace, where he worked first in the Higher Education Office and then in the State Press Office of the Hamburg Senate. This was also the time when he had to give up his “programmed hermit existence,” a phrase he used to describe his “inner separation from his environment.” Instead, he had to come to terms with his own history and, on the basis of his own experiences, made it his task to build bridges between Israel and Germany. He also pursued this goal in his activities in the context of the visiting program for former Jewish Hamburg residents of the Senate of the Hanseatic City, for which Rudolf Heymann was active and also invited guests from Uruguay. Steffi and Kurt Wittenberg also returned to Germany in 1951 from the USA, where they had lived since 1948, and began a new life in Hamburg. Since Steffi Hammerschlag (later Wittenberg) had neither German nor Uruguayan citizenship at the time she left for the U.S., she had a return permit issued in August of 1947.

[Read More: Getting in touch with the old homeland in Uruguay]

[Read More: Getting in touch with the old homeland in Uruguay]

An ambivalent relationship with Germany.

Rapprochement – a difficult process

Rapprochement – a difficult process

“It was the experience of this performance that made me commit the stupidity I should not have committed. On Sunday morning I went to Gryphiusstrasse, to the apartment building where we had lived during my school days in the Third Reich. But it was not the house that I was interested in, I wanted to walk “the way through the cold” again, the way that I so often walked and that led to the Sabbath Anatevka. So I slowly began to walk the streets so familiar to me. I knew that the temple had not been destroyed on November 10, 1938, like the large synagogue on Bornplatz next to the Talmud Torah School. The reason: the temple was and is next to the police station, and so the “spontaneous popular rage” was directed at the inside of the building. After about 10 minutes I left Leinpfad on the right, crossed the Alster, on the left was the former school building of the Lehmann sisters, and via Mittelweg I came to Oberstrasse. The first thing I saw was the lantern in front of the police station, and then it stood before me, the building that I had carried with me to South America, and whose photograph was reproduced in my prayer books. The large seven-branched candelabrum set into the façade shone as brightly as ever. But the inscription “My house shall be called a house of prayer for all nations” had disappeared; instead, there were huge metal letters reading NORDDEUTSCHER RUNDFUNK.”

Forced emigration led to a (permanent) feeling of being uprooted for many. While the feelings toward the new homeland, as Detlef Aberle describes in his interview with the Workshop of Remembrance [Werkstatt der Erinnerung], could be characterized by gratitude, the relationship to the former homeland was often difficult, as it was always involved a confrontation with the past and thus usually with immeasurable pain and suffering. In the before mentioned interview, Detlef Aberle also describes ambivalent feelings: a great familiarity in view of the places he knew so well from his childhood and youth and, at the same time, alienation at the destruction and the way these places and the recent past were dealt with. Nevertheless, Detlef Aberle was one of those who could have imagined a (temporary) return to his former home Germany, or Hamburg. A step he nevertheless did not take, he remained a resident of Buenos Aires. (Business) trips, however, repeatedly took him to Europe and Germany, where he also visited his native city Hamburg.

Encounters – Angela Merkel on a visit to Buenos Aires

Encounters – Angela Merkel on a visit to Buenos Aires

The Templo de Libertad was built in 1931, and a year later Eberhard Friedrich Walcker equipped it with a Walcker organ built in Ludwigsburg especially for this synagogue. Today, it is one of a total of three Walcker organs that have survived worldwide, as all other organs had fallen victim to destruction by the Nazis. Along with several other synagogues in the Belgrano neighborhood, the main residential area of German-Jewish immigrants, the Liberal temple was used by the Ashkenazi and German-speaking communities. Its importance as a site of German-Jewish cultural heritage is reflected by the fact that the organ’s 2016 restoration was funded by the German Foreign Office’s Cultural Preservation Program, and the organ’s inauguration was attended by German Chancellor Angela Merkel. In her speech, Merkel emphasized the importance of Argentina as a place of refuge for persecuted Jews during the Nazi era, and she described the synagogue as a “bridge between Argentina and Germany.”

Rapprochement – a new passport

Rapprochement – a new passport

After the end of the Second World War, German-Jewish refugees asked themselves to what extent a “normal relationship” with their former German homeland was possible, because the experiences of persecution, exclusion and murder of individual family members weighed so heavily. Carola Silberberg (née Strauss), who was born in Hamburg on October 13, 1889, had been able to escape to Buenos Aires / Argentina, where her passport was reissued in 1941. Even in exile, the clearly visible “J” stamped on her passport discriminated against her as a Jew according to the Nazi racial laws and made it clear that she was not considered a member of the Nazi ethnic community. Despite the insults and harassment, persecution and exclusion by the German state during the Nazi era, Carola Silberberg decided in 1957 – along with her husband Theodor Silberberg – to once again assume the citizenship of the Federal Republic of Germany. On September 25, 1957, she received her new German passport – issued by the Consulate General in São Paulo, where she had moved in the meantime to (re)unite with other members of the Silberberg family. While some German-Jewish families were open to an engagement with German society and history, for others such a rapprochement was difficult. Not only did it mean revisiting their own experiences of exclusion and expulsion, it also involved coming to terms with the fact that (their) family members had been murdered. Some of the refugees were the only ones who had survived in exile and only learned about the deportation and murder of their families by the Nazi regime after the end of the Second World War.

Encounters – A Visit to Germany (1962)

Encounters – A Visit to Germany (1962)

The ambivalent reactions of former German Jews to the visits of West German government delegations to Brazil illustrate how difficult the rapprochement with their “old homeland” was for many German-Jewish refugees in São Paulo. At the same time, some German Jews did visit the budding FRG. In 1962, for example, Rabbi Dr. Fritz Pinkuss, former Chief Rabbi of Heidelberg, later Chief Rabbi of the Congregação Israelita Paulista in São Paulo, traveled through Germany at the invitation of the Jewish Weekly. In an interview published by broadcaster SWR titled “Conversation about the relationship between Jews and Germans,” Pinkuss tried to describe his relationship to his “old homeland” Germany. As a “native German and European,” as Pinkuss put it in the interview, he praised contemporary developments in the Federal Republic and saw, in particular, the breaking up of the “narrow national feeling of the past” as a positive development that was central to the establishment of a modern Europe. At the same time, he stressed that “no one can be asked to forget,” referring to the special responsibility that fell to the Federal Republic of Germany and the German people. He considered “new encounters between Germans and Jews” fundamental and necessary in order to ensure a responsible approach to history. German youth occupied a key position for him in this context, since in his view they were the guarantor for a “new Germany, a new Europe.” As a Brazilian and a Jew, he also defended in the interview the arrest of Adolf Eichmann in exile in Argentina and his transfer to and sentencing in Israel, as he saw this as a just, criminal prosecution of the National Socialist atrocities that Eichmann had organized.

Rapprochement – a difficult process

Rapprochement – a difficult process

The notes read by Rudolf Heymann in this excerpt from the interview he gave to the Workshop of Remembrance [Werkstatt der Erinnerung] in 1995 speak of an attempt to come to terms with his own ambivalent relationship to his former and new homeland. As Rudolf Heymann emphasizes, his return to Germany was not for economic reasons and therefore implied for him a confrontation with the past, with his own history. While he still avoided visiting the graves of his relatives, he could not avoid encounters with West German majority society and its way of dealing with the legacy of National Socialism. In addition to the emotional burden, the difficulties of a formal “rapprochement” became evident, for example, in regaining German citizenship. An example of this is the letter from Kurt and Steffi Wittenberg of November 1950, which they sent to the district president of Würzburg before they crossed from Texas to Hamburg.

Encounters - Visits and Activity in Montevideo

Encounters - Visits and Activity in MontevideoEven after her return to Hamburg, Steffi Wittenberg traveled regularly to Uruguay since the end of the 1970s - in 1957 she visited her parents for the first time together with her then two-year-old son Andreas Wittenberg. The importance of Uruguay to the family has remained with subsequent generations, two of Steffi Wittenberg's grandchildren spent time in Uruguay, thanks to continuing ties of kinship and friendship.

After the establishment of the military dictatorship in 1973 Steffi Wittenberg also got involved with human rights work on behalf of political prisoners after. She was also motivated by her own experiences as an immigrant in Uruguay and wanted to give back some of the solidarity she had experienced there. With the help of numerous letters and talks, and in cooperation with Amnesty International, she succeeded in persuading politicians and other representatives of the Federal Republic of Germany to speak up for political prisoners to the Uruguayan military.

[Read More: The Legacy of Emigration]

[Read More: The Legacy of Emigration]

Remembering – leaving traces

Remembering – leaving traces

The “Stolperschwelle” [stumbling threshold] as a special variation of the commemorative form of the Stolpersteine [stumbling stones] was laid in 2017 in the presence of government officials, representatives of various embassies and Anna Warda as a representative of the foundation “SPUREN – Gunter Demnig” as the first Stolperstein outside of Europe. The inscription on the “Stolperschwelle” is a quote from former Pestalozzi School student Margot Aberle Strauss: “The school gave me a sense of security and eased the trauma of emigration.” As the quote makes clear, the “Stolperschwelle” is a reminder of arriving in a new country and thus successfully escaping Nazism. At the same time, however, it exhorts us to keep alive a memory of those who did not succeed in emigrating and who were deported and murdered by the National Socialists – just like the Stolpersteine in Germany and Europe, which are laid at the last voluntarily chosen place of residence.

Preserving – A Living Heritage

Preserving – A Living Heritage

“…it’s much easier to connect than if someone – let’s say – had a different past…”

The “chicas del lunes” (Monday girls) are volunteers at the Hogar Adolfo Hirsch, a retirement home for German-speaking Jewish immigrants founded in 1940 by the Aid Organization of German-speaking Jews (Asociación Filantrópica Israelita) in San Miguel, north of the Argentine capital Buenos Aires. Many of the residents as well as the volunteers had to flee Germany in the 1930s due to Nazi persecution, many via the port of Hamburg. The Aid Association [Hilfsverein] assisted the arrivals with entry formalities, finding housing or work. Many felt and still feel connected to the Aid Association and are therefore involved as volunteers. In the Hogar Hirsch, the residents and helpers thus preserve “a piece of Germany,” as Corinna Below describes it in her interview project of the same title. The shared language and culture are a unifying element, as are the shared emigration experiences and memories.

Remembering – Traces in São Paulo and Hamburg

Remembering – Traces in São Paulo and Hamburg

The traces German Jews left in São Paulo and Hamburg are manifold. In the Jewish cemetery in Tristeza, Porto Alegre, for example, there is the grave of Moses Goldschmidt. His hopes, which he had formulated in a letter to his daughter in Mumbai / India, to survive the war and to reunite his family in one place, did not come true. He died August 12, 1943. His memoirs were found in his estate and were published in 2004 by his family under the title “Mein Leben als Jude in Deutschland 1873 – 1939 [My Life as a Jew in Germany 1873 – 1939].” The graves of Walter and Gerda Silberberg can be found at the Butantã Jewish Cemetery, São Paulo. Walter Silberberg died April 11, 1987 and Gerda Silberberg March 25, 2003. Throughout their lives they felt connected to the Congregação Israelita Paulista in São Paulo. In addition to gravesites, there are also other places of remembrance in São Paulo, such as the Homenagem em Memóriam às Vítimas do Nazismo (Memorial to the Victims of Nazism) at the Butantã Jewish Cemetery or the newly opened Jewish Museum in São Paulo, which was reopened in 2021 and also commemorates the history of German-Jewish refugees.

The laying of Stolpersteine [“stumbling stones”] in Hamburg for individual members of the Silberberg family also created sites of remembrance in Hamburg. Researcher Sonja Zoder of the initiative “Stolpersteine Hamburg – Biographische Spurensuche” published an extensive family biography in April 2018, which remembers the family members who did not manage to emigrate to Brazil and perished in the Shoah, such as Henny Silberberg (murdered in Theresienstadt in 1942), Rosalie Strauss (murdered in Theresienstadt in 1943) or Peter Silberberg (murdered in Auschwitz in 1942). The Stolpersteine thus render the history of persecution and extermination, but also of expulsion and escape – in this case to São Paulo – visible in Hamburg.

Preserving - A Living Heritage

Preserving - A Living Heritage