Our second online exhibit organized as part of the edition of key documents in Jewish history is dedicated to the topic of “migration.” After Bremen, Hamburg developed into an important port for millions of emigrants from German-speaking central Europe to America following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Among the roughly 100,000 Jews who emigrated from the German territories to North America between 1820 and 1880, it was mainly Jews from the province of Poznan (Posen) who boarded a ship in Hamburg. In the 1870s, migration to America shifted from central Europe and the British Isles to southern and eastern Europe. Jews from eastern Europe made up a considerable share of this transatlantic mass migration. Between 1880 and 1914 more than two million Jews from eastern and east central Europe resettled, mainly in the United States. More than half of all Jewish migrants from eastern Europe to America embarked on their transatlantic voyage in either Hamburg or Bremen.

This exhibition is divided into six stations in order to trace the migrants’ journey. It begins with their departure from the Old World, then follows their journey to the emigration port of Hamburg and finally to their arrival on Ellis Island. In addition to this thematic-chronological narrative (vertical), each individual station of the journey can also be explored further (horizontal). Texts were written by Tobias Brinkmann.

In the 1880s, the two leading German shipping companies, HAPAG and Lloyd, successfully developed the lucrative eastern European passenger market. They profited from Imperial Germany’s convenient geographical location since eastern Europeans had to cross it on their way to the North Sea ports. […] Hamburg’s 1892 cholera epidemic lead to a reorganization of transit migration from eastern Europe. In 1893, American authorities stipulated disinfection and several days of quarantine for all Russian migrants in their European port of departure. […] HAPAG and Lloyd established “checkpoints” at the most vital railroad border crossings, where all migrants had to undergo disinfection and a medical examination in compliance with the provisions of American immigration law. […] The checkpoint system cemented the monopoly on the eastern European migrant market held by the two German shipping lines. (Source: Tobias Brinkmann, “On the Road with Ballin—Experiences Made by a Russian Emigrant”)

These attractive poster advertisements by major shipping companies do not give a realistic impression of everyday life during a transatlantic crossing. The posters were addressed to well-off businessmen and tourists traveling in the opulent first class or very comfortable second class. The great majority of simple migrants spent their journey below-deck in the bilge of the gigantic ocean-going ships. Steerage passengers were accommodated in large dormitories separated by gender. In the 1890s German and American authorities defined hygienic standards, limiting the number of people allowed in a dormitory. Ships were inspected regularly. Each passenger was entitled to their own bed and a fixed number of meals. While the passage was a fascinating experience especially for children, women were often exposed to sexual harassment by the ship’s crew members. During the stormy winter months many passengers complained of seasickness. After 1900 the journey from Hamburg to New York no longer took more than a week.

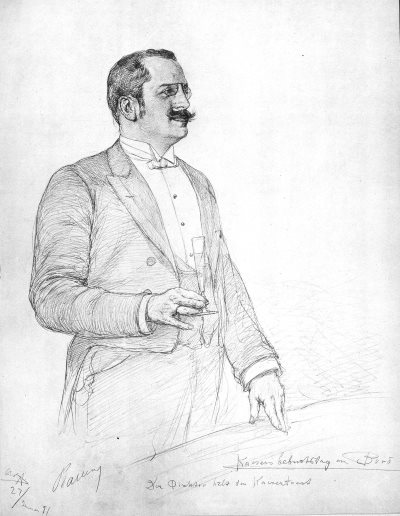

Albert Ballin, the son of a Jewish ticket agent who had emigrated from Denmark to Germany, grew up in Hamburg in simple circumstances. He took over his father’s agency in the 1870s. In the early 1880s he and his English business partner established a budget shipping line offering direct service from Hamburg to New York – to great success. The HAPAG (Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft) swallowed up its tiresome competitor in 1886. As part of the merger deal, Ballin secured the post of director of HAPAG’s passenger service for himself. He aligned HAPAG’s business with the growing market in eastern Europe and organized a cartel of leading European shipping companies. In 1899 Ballin was appointed HAPAG’s general director. That year, HAPAG became the world’s largest shipping line and it continued to expand. Ballin made a point of providing comfortable accommodation for simple migrants. Along with cargo shipping, steerage tickets made up HAPAG’s core business. Before the First World War, HAPAG was Hamburg’s largest employer. Ballin had a difficult relationship with labor unions and he was an outspoken opponent of the Social Democratic Party. Although a member of Hamburg’s Jewish congregation, he kept a distance to Jewish life.

HAPAG and its competitors ran daily small advertisements in various newspapers in Germany, the United States, and especially in eastern Europe. These advertisements informed readers about the price of the passage and about new routes. HAPAG emphasized its position as the leading global shipping line and its modern fleet. Most passengers bought their tickets from agents who closely cooperated with HAPAG. The ticket price covered the passage and usually also train travel to Hamburg.

The increase in migration from eastern Europe to North America around 1880 was a result of the growing demand for cheap labor. The expansion of the railway system into previously barely developed eastern European regions enabled millions of people to migrate westward after 1860. Many migrated within eastern Europe, particularly to industrial centers like Warsaw, or they hired themselves out as seasonal agricultural labor in Prussia. After 1880 a growing number of eastern Europeans resettled to North America. They traveled by train via Berlin or Leipzig to port cities like Hamburg, Bremen or Rotterdam. Railways and modern steamships shortened their journey from months to weeks. The train journey from most places in eastern Europe to Hamburg took no more than two to three days. In most cases, however, it took migrants at least a week to get there because they had to avoid official border controls. Unlike seasonal labor migrants, emigrants had to obtain official permission to leave. In Russia it was difficult as well as expensive to apply for an emigration passport. In the Austro-Hungarian Empire young men who evaded military service were severely punished. Therefore many emigrants crossed the German eastern border illegally with the aid of smugglers. The Prussian government tolerated this practice because it did not have sufficient personnel to control the border effectively. After 1893 German shipping companies set up checkpoints at the border and organized the migrants’ onward journey to the ports. Many migrants now traveled in sealed “emigrant trains” directly to their port of departure. After 1900 return migration increased noticeably. Most returnees had not failed abroad, but had worked in America just for a year or two. Having returned home, they now invested the wages they had earned overseas in small businesses.

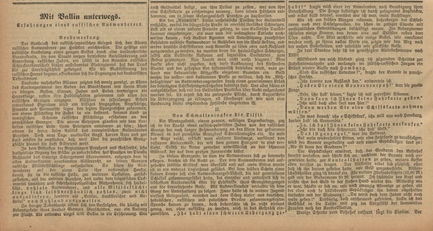

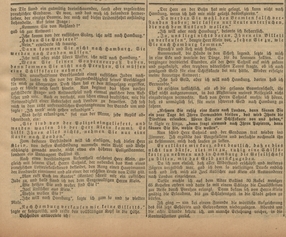

On December 10, 1904, the police inspector in charge of HAPAG’s emigration halls at the port of Hamburg, Wenzel Kilian Kiliszewski, noticed a man calling himself “Jossl Kalischer.” Claiming to be a Jewish migrant from the Russian empire, he turned out to be Julius Kaliski, editor of the Social Democrat’s daily newspaper Vorwärts. Although his disguise aroused suspicion, Kiliszewski was unable to prove Kaliski had broken any laws, and he left the emigration halls a free man. Two days later, on December 12, 1904, Kiliszewski informed HAPAG’s management about the incident. A reply issued the same day read: “Our general director was of the opinion that it would be best not to pay too much attention to the matter...” Vorwärts announced the publication of Kaliski’s articles on the morning of the same day. Between December 20, 1904 and January 10, 1905, six articles titled “On the Road with Ballin” describing Kaliski’s journey from the Prussian border near Tilsit in East Prussia to Hamburg were printed. In order to experience the treatment of eastern European migrants during their passage through Germany on their way to the USA, Kaliski disguised himself as a Jewish migrant of modest means. His articles document the various stations of his journey from the Prussian-Russian border to HAPAG’s emigration halls at the port of Hamburg. Read on >

Between 1903 and 1906 a wave of pogroms in the south of today’s Ukraine resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Jewish victims. The Russian government was unable to effectively contain the violence. The Aid Organization of German Jews dispatched representatives to the region to document the pogrom’s effects and help the most desperate victims. Among those the so-called “pogrom orphans,” children who had lost their parents to the violence, were given particular attention. In 1906 the Viennese Jewish women’s rights activist Bertha Pappenheim traveled to Russia in order to take a group of pogrom orphans to Germany. The Aid Organization coordinated their adoption in various European countries. In subsequent years the Aid Organization organized further transports of pogrom orphans. Some of the orphans traveled via Hamburg.

In close cooperation with several Jewish congregations, the Aid Organization established a tight network of shelters and accommodations for Jewish migrants along their main travel routes. The many photographs in the Aid Organization’s reports illustrate that gender was an important criterion. Men and women were put up separately. Children usually slept with their mothers. The photographs in the annual reports were meant to show that the Aid Organization took care of the migrants. It is noticeable that the photos show mainly children. Many Jews emigrated with their entire family, and they usually had many children. Images of children were supposed to move potential donors to support the Aid Organization.

These images from Tilsit, a border town in the north of East Prussia, and from the port city of Stettin in Pomerania were meant to illustrate that the migrants did not want for anything. The image from Tilsit shows four women in a shelter. The interior is reminiscent of a middle-class dwelling. On the table there is a lamp, a loaf of bread, a bottle of water, a mug and a menorah. The image from Stettin is even more direct. A family has gathered around the table at the beginning of the Shabbat. The parents are saying the prayers. The image demonstrates that the Aid Organization and the Jewish congregations took the migrants’ religious needs seriously. The Aid Organization provided kosher food to Jewish migrants along their main travel routes. Their relief work relied mainly on donations. These images were intended to motivate readers of the reports to support the Aid Organization. Without donations – this was the implicit message of these at times moving images – it would not have been possible to address the particular needs of Jewish migrants.

In 1894 Mary Antin (born Maryasche Antin) from the Belarusian town of Polotzk, her mother and three siblings traveled via Hamburg to Boston, her father already having gone ahead. Immediately after her arrival in 1894, Mary Antin gave an account of her voyage in a letter to her maternal uncle, Moshe Hayyim Weltman in Polotzk. […] The excerpt presented here, which describes the disinfection in Ruhleben, became well-known through the more reflective and more emotionally charged English version of 1899 because Mary Antin reused literal quotes from this version of the letter in her 1912 autobiography titled “The Promised Land.” The book was a great success, it went through several editions and was translated into German as early as 1913. Read on >

Hamburg’s Jewish congregation took care of the Jewish migrants, yet they had no interest in their long-term or permanent settlement in the port city. One important figure in this effort was Daniel Wormser (1840–1900), a teacher who had founded the Israelite Association for the Support of the Homeless in 1884. He organized the supply of kosher food. Hamburg’s authorities regularly contacted the congregation when Jewish migrants got into trouble. It was very important to the congregation that Jewish migrants did not become a burden to public authorities. It posted representatives at the port and as of 1902 also at HAPAG’s emigrant facilities. It also cooperated closely with the Aid Organization of German Jews, who coordinated support for migrants from their office in Berlin. Like many other Jewish congregations in Germany, the congregation distinguished between needy persons and professional “schnorrers.” Jewish congregations in Germany exchanged lists with personal descriptions of the latter. Hamburg’s Jewish congregation helped those migrants in particular who fell ill during their journey, fell victim to swindlers or had to return home involuntarily.

The Israelite Association for the Support of the Homeless was founded in Hamburg by Daniel Wormser in 1884. The association provided mainly kosher food and clothing for Jewish migrants from eastern Europe who embarked on an overseas journey in Hamburg. It was funded by donations and received subsidies from the Jewish congregation and Jewish associations such as the Henry Jones Lodge. The reporting year 1899 / 1900 saw the arrival of a number of male and female migrants from Galicia. The report mentions that the Russian migrants were staying in basic accommodations at the port’s America Quay. The HAPAG emigrant facilities at Veddel were still under construction at this point and only opened in 1901. The text also alludes to the problem of the “mission.” This refers to Christian missionaries who tried to convert Jewish migrants. The missionaries’ methods were controversial, and the number of Jewish converts remained relatively low.

The Hamburger Fremdenblatt was one of the major daily newspapers in Hamburg around the turn of the century. In November 1901 Hamburg’s Israelite Association for the Support of the Homeless and the Jewish congregations of Breslau organized a gathering of Jewish congregations and associations from all over Germany in Breslau. Their goal was to establish a nationwide Jewish relief organization tasked with coordinating support for Jewish migrants – and especially return migrants, who often were destitute. This newspaper clipping shows that the Aid Organization for German Jews essentially grew out of an initiative from Hamburg and Breslau. The latter was an important transit point for Jewish and other migrants from Galicia en route to the United States and Western Europe.

The Israelitisches Familienblatt was a weekly paper published in Hamburg. The paper was distributed throughout Imperial Germany. Jewish life in Hamburg was one of the main topics of its reporting. This clipping documents a visit to the newly opened HAPAG emigrant facilities at Veddel by representatives of the Israelite Association for the Support of the Homeless and the Henry Jones Lodge, of which many prominent Hamburg Jews were a member. The small delegation visited the kosher kitchen, the dining hall for Jewish migrants, and the small synagogue that was still under construction at the time. Police officer Wenzel Kilian Kiliszewski led the Jewish visitors through the facilities. Kiliszewski was head of the emigrant facilities’ police force and had been in charge of emigrants at Hamburg’s port since the 1890s. Between 1891 and 1910 he took several trips to eastern Europe on behalf of the Hamburg senate in order to gather information on the main routes of migration. His detailed reports contain antisemitic comments.

In contrast to the very positive description of the facilities printed here, migrants repeatedly complained about a lack of space and insufficient hygiene. The Jewish relief committee also repeatedly asked Daniel Wormser to accommodate single individuals at his house. (Karin Schulz, Hamburg und die jüdische Auswanderung. Part II: Von 1882 bis 1914, in: Die Juden in Hamburg 1590 bis 1990. Wissenschaftliche Beiträge der Universität Hamburg zur Ausstellung „Vierhundert Jahre Juden in Hamburg“, ed. by Arno Herzig in cooperation with Saskia Rohde, Hamburg 1991, p. 472.)

This call for donations by the Israelite Association for the Support of the Homeless was published to coincide with the Jewish New Year in the fall of 1906 and inserted into issue No. 36 of the Israelitisches Familienblatt (September 6, 1906). That year numerous pogroms had occurred in the southern provinces of the Russian empire, especially in the area of today’s Ukraine and Moldova, in the course of which dozens of Jewish women, men and children were killed. While the call for donations does not make a direct connection between the pogroms and migration, it appeals to its readers to support eastern European Jews – by a donation to the Israelite Association for the Support of the Homeless. The donors’ names were to be published in the No. 37 of the Israelitisches Familienblatt (September 13, 1906).

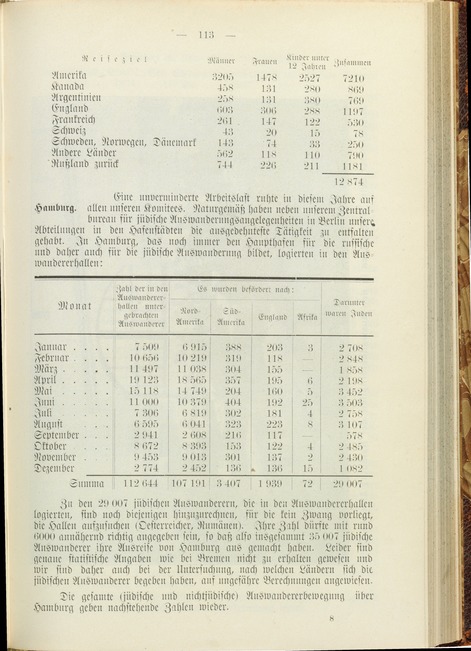

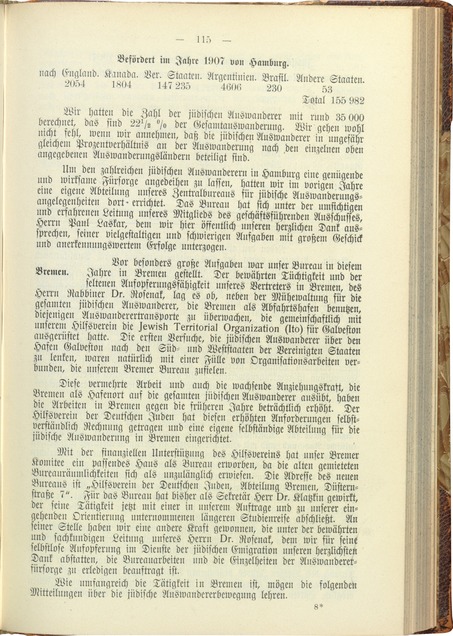

In 1907 the Aid Organization of German Jews opened a local office in Hamburg in order to support the work of the Israelite Association for the Support of the Homeless and Hamburg’s Jewish congregation. The reason for this was the considerable increase in migration from eastern Europe to the United States. In 1900 more than 60,000 Jews immigrated to the United States. In 1906 and 1907 respectively their number was 150,000. The enormous increase in Jewish migration from eastern Europe explains why the Aid Organization came to support the Jewish aid associations in Hamburg.

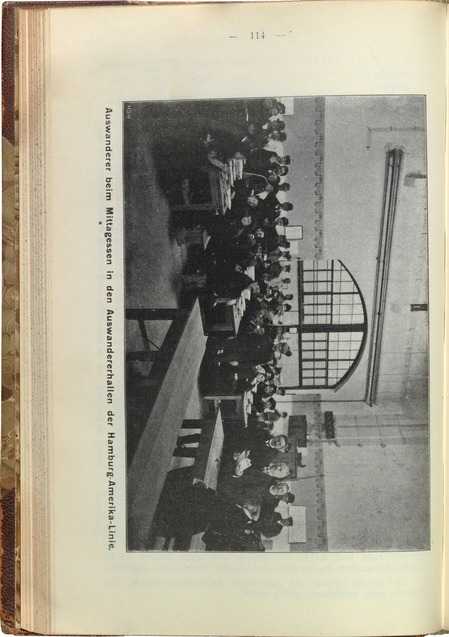

The business reports of the Aid Organization of German Jews were published annually since 1902 and documented in great detail the emigration trends among eastern European and especially Russian and Galician Jews. […] Between 1901 and 1918, the Aid Organization became the leading organizer of Jewish emigration from eastern European and, as part of the network of Jewish aid organizations cooperating internationally, primarily took charge of Jewish emigrants’ transit through Germany. […] The local Hamburg chapter was headed by Paul Simon Laskar (1857–1926), who had been a member of the Aid Organization’s executive committee since 1901. Read on >

As in many other port cities, the greatly increasing number of migrants in transit after 1880 at times led to chaotic circumstances in Hamburg. Most migrants had to wait for several days for the departure of their ship. Those who could afford it stayed at a bed and breakfast in the city center. These were often overcrowded and offered a low standard. Other migrants slept on the streets or in train stations. Following a cholera epidemic for which Russian migrants were falsely blamed, U.S. immigration authorities in 1893 demanded that all Russian migrants undergo a disinfection procedure and be quarantined for several days before their departure. Consequently, Russian migrants in transit were put up in primitive barracks at Hamburg’s America Quay as of spring 1893. Growing competition but also concern for standards of hygiene led to the decision by HAPAG’s management to build a modern “emigrant city” at Veddel, in the southern part of the port. It opened its doors in 1902. Now most emigrants arrived at the HAPAG emigrant facilities directly by train without ever setting foot in one of Hamburg’s train stations. Immediately after their arrival they were given a medical exam and disinfected. On the complex’s “clean” side, HAPAG provided its passengers with a relatively high level of comfort. Men, women and small children were accommodated in separate dormitories. There even was a small synagogue. Jewish passengers were provided with kosher food thanks to support from Hamburg’s Jewish congregation. From the emigrant facilities migrants walked and pulled carts to the nearby America Quay. After 1900 Jewish passengers were also able to obtain kosher meals during the voyage.

This floor plan shows the emigrant facilities after the building of an addition that was completed in 1907. It illustrates the facilities’ separation into a “clean” [rein] and an “unclean” [unrein] complex. In the reception building a physician examined all migrants before they had to undergo disinfection separated by gender. One of the smallest buildings is the synagogue located in the southern section of the facilities on the “clean” side. People suffering from an infectious disease or showing noticeable symptoms were quarantined in a separate “observation unit.” Otherwise the accommodations consisted of pavilions separated by nationality, religion, and gender.

These house rules written in German and Hungarian provide an insight into everyday life at the emigrant facilities. Only few migrants in transit spoke German. In addition to Hungarian, the most commonly spoken languages among them were Polish, Yiddish, Czech and Croatian.

Migrants in transit had to pay 2 Mark per day for room and board. Those who could afford to pay more stayed in hotels that were part of the emigrant facilities. Their rates were lower than those in the city and probably did not entirely cover HAPAG’s expenses. The information provided in German, Hungarian, Polish, Russian, and Hebrew clearly proves that most passengers came from eastern Europe. There is no information in English.

These two information texts date from the 1920s. During the First World War the emigrant facilities served as a military hospital. In 1921 part of the complex was reopened to HAPAG passengers. Having lost almost its entire fleet during the war, HAPAG in 1921 once again began service to North America in cooperation with the American Harriman Lines. In the same year, the U.S. Congress largely excluded eastern and southern Europeans from immigration to the U.S. Many HAPAG passengers traveling to North, South and Central America in the 1920s were German emigrants. The reference to family members accompanying migrants to see them off provides an interesting detail.

The main author of this article on Jewish emigration was Bernhard Kahn (1876–1955), who worked for several Jewish aid organizations in Germany and the United States. In 1905 he was executive director of the Aid Organization of German Jews. The text on Ellis Island was written by Theodor Vogelstein (1880–1957). In 1906 he taught political economics in Munich. In 1918 he was among the founders of the left-wing liberal Deutsche Demokratische Partei [German Democratic Party, or DDP]. This text provides extensive and differentiated information about Jewish migration from eastern Europe. The photographs of migrants and members of the Aid Organization and Jewish congregations taken in Hamburg, Bremen, and Berlin specifically for the article are a particularly valuable source. The pictures taken in Ruhleben (near Berlin) are the only known photographs of that facility.

Johann Hamann (1859–1935) opened his photo studio in Hamburg’s Gängeviertel district in April 1889. At this point in time, snapshots taken outside the studio and the reproduction of photographs became easier thanks to the introduction of new technologies. Hamann’s work as a photographer consisted of both studio portraits and a photographic documentation of the city and its inhabitants. He also took photographs of animals in Hamburg’s zoo, which were used in classrooms. Hamann began doing work commissioned by the Hamburg-America Line in 1899, first portraying its captains and later also its ships. He carried out this work with the help of his son, Heinrich Hamann (1883–1975), who began following in his father’s footsteps. The photographs Hamann and his son took in HAPAG’s emigration facilities in 1909 also were commissioned by the shipping line. Some of the images were published by Walter Stahmer the following year in the brochure “Die Auswandererhallen in Hamburg” [The Emigration Facilities in Hamburg]. Heinrich Hamann continued taking on commissioned work for HAPAG, providing photos for its travel and advertising brochures, among other things.

The entire collection of Hamann’s photographs of the emigrant facilities is located in Hamburg’s State Archive today.

Upon arrival all emigrants were given a medical exam and disinfected before they were allowed to enter the “clean” section of the emigrant facilities. Previously these medical checks had been carried out immediately after the border crossing, for example in Ruhleben near Berlin.

This much reproduced image can also be found in the Aid Organization’s annual report for 1907. It was taken in the emigrant facilities and shows Hamburg representatives of the relief organization with Jewish emigrants and HAPAG staff. We do not know why exactly this picture was taken, but it was used to show the Aid Organization’s donors that the organization’s staff members took care of the migrants and provided professional advice to them. Looking at the photo, it is noticeable that all the male emigrants are wearing hats (as do the HAPAG employees) while the representatives of the Aid Organization do not. Most likely the Jewish families in this picture were Orthodox. The photo’s long exposure time explains why the faces of the children and women in the front row are blurred. Children often found it hard to stay still for more than a minute.

This handwritten program documents the prayer service that was held on the occasion of the opening of the synagogue at the America Quay on September 3, 1896. Following a cholera epidemic in Hamburg in the spring of 1893, the American immigration authorities demanded that all Russian immigrants be quarantined for several days before they embarked on their journey to North America. This in turn rendered it necessary to cater to the migrants’ religious needs. Daniel Wormser and the Jewish congregation had advocated for the building of a synagogue and the establishment of a kitchen run according to Jewish dietary laws.

This image shows the interior of the small synagogue in the emigrant facilities. Emigrants were housed according to their religion; in addition to a synagogue, there was a Jewish dining hall, a kitchen for the preparation of kosher food, and dormitories for Jewish men and women. Christian migrants were housed separately; there was both a Catholic and a Protestant chapel at the facilities.

This image shows a common room in the emigrant facilities. This is where Jewish passengers waiting for their passage spent the day, especially during the winter months. The women’s and men’s heads are covered. The children’s faces are blurred because they could not manage to stay still long enough during the photo’s exposure time.

These images show the Jewish emigrants’ dining hall, which has been documented in other photos as well. In the image showing a farewell meal, Hamburg representatives of the Aid Organization of German Jews can be seen in the foreground on the right. This image of a farewell meal also appeared in the Aid Organization’s annual report for 1907.

Using a shorter exposure time on a sunny day allowed Hamann to show an unusual view of the everyday hustle and bustle in the emigrant facilities’ “clean” section. In the foreground there are two well-dressed men wearing bowler hats, most likely HAPAG employees. A larger group of men and women from eastern Europe are forming a line. In the background we can see more HAPAG employees standing. Although their luggage is not shown in this picture (with the exception of the small group on the right in the foreground), this group is probably waiting to board their ship. A sign on pavilion no. 9 written in German, Hungarian, Polish, Russian, and Yiddish points to the place of embarkation. Pavilions no. 9 and 4, shown on the left, housed dormitories, common rooms, and sanitary facilities. The building shown on the right contained the disinfection facilities all migrants had to pass through before they were allowed into the complex’s clean section. In the background on the left one of HAPAG’s administrative buildings can be seen.

These emigrants are boarding a ship which strikes the viewer as relatively small. Most likely it carried passengers to one of the large ocean steamers that were the usual means of transportation for the overseas passage since 1901.

Until 1914 most immigrants first stepped onto American soil in New York City. Before the immigrant inspection station on Ellis Island opened in January 1892, immigrants were processed at Castle Garden, a vast wooden building located at the southern tip of Manhattan. It was relatively easy to avoid inspection in the large crowds. Many immigrants were unprepared for the hustle and bustle of the huge city just outside the doors of Castle Garden. Quite a few of them lost all their savings to swindlers only hours after their arrival. Ellis Island heralded a new phase in American immigration history. All passengers traveling in the cheapest class had to undergo inspection in order to ensure that they were healthy and in compliance with immigration regulations. At the same time, migrants were protected from various kinds of swindlers at Ellis Island, and they could seek assistance from the staff of Jewish and other relief organizations. A considerable number of European migrants traveled via Canadian ports or other American ports such as Philadelphia, where they were also examined by American immigration inspectors after 1892. Passengers traveling in first and second class were only questioned superficially on board their ship. Even though many migrants felt anxious about the inspection at Ellis Island, only about two percent of all migrants were actually denied entry. HAPAG and the Bremen-based Norddeutscher Lloyd shipping company enjoyed a good reputation with American immigration authorities due to their high standards of hygiene. Accordingly, the rejection rate among their passengers was low. This was one reason why many eastern Europeans took lengthy detours in order to travel via Hamburg or Bremen.

The immigrant landing station on Ellis Island, housed in a large wooden building, opened its doors on January 1st, 1892. In 1897 the building burned down almost completely. The impressive new building was opened in 1900 and still stands today.

This photo shows a group of presumably eastern European immigrants with their luggage in the entrance area of the new main building of the Ellis Island immigrant control station, which was built in 1900. Directly behind the photographer is the landing stage for the ferry with which migrants were taken from the dock in Manhattan or Brooklyn to Ellis Island and which still exists today.

All immigrants underwent a medical exam after their arrival in the United States. A physician inspected passengers in the first and second class on board their ship. Most migrants traveled in the ship’s steerage as third class passengers, however. From the dock in Manhattan or Brooklyn they were taken by ferry to Ellis Island, where they were meticulously checked for certain infectious diseases. In the background there is a board showing Hebrew letters, which was probably used for vision tests.

Immigrants were registered in the large main hall at Ellis Island. U.S. immigration officials checked the names of those immigrating against passenger lists. They recorded the immigrants’ names, place of origin and their destination. Younger women traveling alone were often questioned particularly thoroughly in order to ensure that they were not prostitutes. Immigrants who had to undergo a longer inspection could turn to Jewish and other aid organizations for support. They could also hire a lawyer to represent their interests.

The immigrant inspection station was closed in 1954. The main building and smaller adjacent buildings subsequently stood vacant. On the occasion of the centenary of the dedication of the Statue of Liberty (1886), prominent American figures campaigned for the building of an immigration museum on Ellis Island, in close proximity to the Statue of Liberty. The main building was renovated, and in 1990 the first visitors were admitted to the museum which is run by the National Parks Administration.

In 1889 the “Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal” replaced an earlier building. The vast train station counts more than a dozen platforms. For almost twenty years, this terminal served as one of New York’s most important train stations since there was no direct train connection to Manhattan from New Jersey prior to 1910. Ferries sailing from and to Manhattan docked directly at the train station. Its proximity to Ellis Island also explains why after 1892 this train station also became an important transportation hub for immigrants. Following inspection, immigrants were taken by ferry to the nearby mainland terminal. From there, they embarked on their inland journey without ever setting foot in New York City. After the First World War the train station was mainly used by commuters from New Jersey. It was closed in 1967.

This (colorized) photo postcard sent in 1922 gives an impression of life on New York’s Lower East Side. Around 1860 the neighborhood was called “Little Germany.” By the 1880s, when most German-speaking immigrants had moved north to better neighborhoods, it was mainly Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe who settled on the Lower East Side, becoming close neighbors with Italian immigrants. Around 1905 roughly 350,000 Jews lived in this part of New York alone. Like the Jewish immigrant quarters of Chicago and London, this neighborhood was referred to as a “ghetto” in the vernacular as well as by the American-Jewish public. The name reveals more about the stereotypical perspective taken by many established Jews and many Americans than about the immigrants, many of whom only lived in the neighborhood for a few years. Many of them earned their livelihood as peddlers. Jews particularly specialized in selling fruit from carts, some of which can be seen in the background. In the 1920s most Jewish inhabitants moved from the Lower East Side to other parts of New York, especially to the Bronx and Brooklyn.

Conceptual design: Tobias Brinkmann und Anna Menny. Technical implementation: Daniel Burckhardt. Translation: Insa Kummer

As of: November 16, 2018.