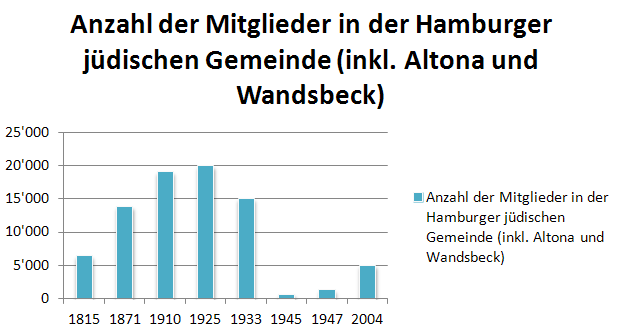

The modern history of Germany’s Jewish minority was characterized by several peculiarities in its social structure, which, generalizing somewhat, could be summarized thus: only in some places, including Hamburg for a time, was the share of German Jews in the overall population ever larger than one percent. From the early modern period until the National Socialist takeover, Jews mainly lived in the Southwest and East of the German territories and, at least since the late 19th century, also in some urban centers such as Berlin or Hamburg. They stood out from the general population as particularly urbanized and also by their remarkable upward social mobility, often the result of a higher level of education. At the same time they displayed specific occupational patterns and a trend towards an ageing population due to a noticeable decline in births. There were considerable regional differences due to varying legal conditions for settlement, starting a family, the inheritance of rights, etc. As early as the 17th and 18th century, Hamburg and Altona became centers of settlement for the Jewish minority. Hamburg’s Ashkenazi Jewish community developed from its beginnings in Altona in 1650 following several failed attempts. At the beginning of the 19th century there was a noticeable population growth in the German-speaking territories when the Jewish population within three decades increased from 260,000 people around 1815 to about 400,000 by the time of the 1848 revolution. This development unfolded in parallel to a growth in the general population — where the increase took a much less pronounced course than among the Jewish minority, however. Since the founding of the Kaiserreich, a fundamental demographic and a resultant economic change was occurring. Around 1870, German Jews lived in about 2,000 small and mid-sized communities and four major communities counting more than 2,000 members (Greater Berlin, Wrocław, Frankfurt am Main, and Hamburg). Compared to the overall population, they were more mobile and therefore clustered in some regional centers. Half of all German Jews lived in Prussia, and after its territory was expanded in 1866 their share rose to 62 percent. A fifth of German Jews lived in Bavaria. Beginning in the 19th century there was a noticeable trend towards urbanization (by 1910 a quarter of all Jews lived in major cities). Of course this trend did not only occur among the Jewish population since it was a result of the new economic perspectives cities offered for both Christians and Jews due to industrialization. Hamburg was home to the largest Jewish community in northern Germany. For a time it had an unusually high share in the overall population at 5 percent around 1800, and it was characterized by a mixed population of both Ashkenazi (6,299 individuals) and Sephardic (130 individuals) Jews. The number of Hamburg’s Jews rose to its highest level in 1925, when there were 19,904 Jewish individuals, which was about 1.7 percent of the overall population. During the years of National Socialist persecution which began in 1933, around 10,000-12,000 Jews emigrated from Hamburg while some remained in the city and survived in so-called “mixed marriages.” A few months after the end of the Second World War a new Jewish congregation counting about 80 members was founded. Today Hamburg’s Orthodox Jewish congregation has more than 2,000 members while the Liberal congregation founded in 2004 has roughly 500 members.

The expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula in the 15th century and from most cities and numerous territories in the Holy Roman Empire in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, which led to the formation of Landjudenschaften, were of central significance for Hamburg’s Jewish history. Jewish settlement in Hamburg began at a time when other cities were expelling their Jewish population. Thus Hamburg’s Jewish history begins relatively late and at a very unusual time for a city. In the course of the 16th century a demographic turn occurred, and urban communities once again grew. Altona and Hamburg now became significant: around 1600 Ashkenazi Jews were allowed to settle in the hamlet of Altona. In 1612 they were granted a so-called Generalgeleit, and within a decade they created a functioning community structure counting 30 Jewish families. From Altona the Ashkenazi Jews tried to establish themselves in Hamburg as well.

In the last third of the 16th century, Hamburg became a popular trading place for English and Dutch merchants as well as a refuge for those fleeing religious persecution in the Iberian Peninsula, most of whom migrated to Hamburg via Amsterdam. They were so-called “New Christians,” i. e. baptized Jews (cristãos novos, conversos, Marranos) belonging to the group of Sephardic Jews. The Portuguese, still nominally Catholic at this time, became the first Jews permitted to settle permanently in this Protestant port city. In 1595 there most likely were seven Portuguese families living in Hamburg; in 1609 their number had increased to 98 individuals. When these migrants reconverted to Judaism, however, the city assembly demanded their expulsion. The city prevented this, and they were allowed to remain in Hamburg as long as they did not establish their own Jewish infrastructure. The Sephardic Unified Congregation founded in Hamburg in 1652 counted about 600 members.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Hamburg and Altona were two central places of settlement for German Jews. Following several failed attempts, Hamburg’s Ashkenazi Jewish community developed from Altona beginning in 1650. In 1671 their congregation united with those of Hamburg and Wandsbek to form the so-called triple congregation Dreigemeinde. Hamburg’s Jewish population slowly grew and at the turn of the 19th century had become one of the largest in Germany, counting 6,000 individuals. The share of Jews in Hamburg’s overall population had now grown to more than five percent. In the 19th century their number increased further and eventually more than doubled to 14,000 people.

With emancipation new professions opened up and consequently the occupational profile of the Jewish minority changed. It resulted in their continuous social ascent to the newly emerging bourgeois middle class. Just as earlier restrictions on one’s choice of profession had widely differed regionally, so the change in professions and the willingness among the Jewish minority to change professions varied considerably. For the most part this was due to the fact that the regulations regarding permits for admission to a trade or the acquisition of land and real estate were different from state to state.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, a large majority of Jews was poor. Half of them worked as retail clerks, domestic servants, and day laborers and thus belonged to the lower class. While about half of all German Jews had to be considered poor in 1850, this applied to only 25 percent by 1871. In the course of just one century Jews had become a majority middle class, urban group. Since the Kaiserreich era, about two thirds of the Jewish population belonged to the middle class in terms of occupation, income, and habits. Hamburg’s Jews, too, experienced this social ascent in the 19th century. While roughly two thirds of local congregation members were still considered poor at the beginning of the century, their share decreased rapidly in the course of the 19th century. Moreover, Hamburg was home to several wealthy families forming a small yet stable Jewish upper class.

The non-Jewish German population in Imperial Germany grew more rapidly than the Jewish minority. While the population growth among Jews was mainly a result of immigration from eastern Europe, among the rest of the population it was caused less by migration than by “natural” increase. Most of the roughly 70,000 Jews who had immigrated to Imperial Germany by 1910 settled in major cities like Berlin and Leipzig, where they constituted up to a quarter of the Jewish population. While Hamburg served as a transit stop for up to 109,000 eastern European Jews annually, tight limits on immigration and strict deportation measures ensured that these transiting migrants could not settle permanently in Hamburg. In 1925 only 14 percent of Hamburg’s Jews were foreign-born, most of them from eastern Europe; in neighboring Altona—belonging to Prussia until 1937 — their share was almost 47 percent. Some of Altona’s “eastern Jewish” inhabitants had lived there since the Kaiserreich period; the majority of them had only settled there during the First World War or in the postwar period, however. Largely penniless, many of these new immigrants were in need of support, which they received from the congregations. Although the foreign Jews were legally equal to Hamburg’s long established Jews, they developed a separate social life.

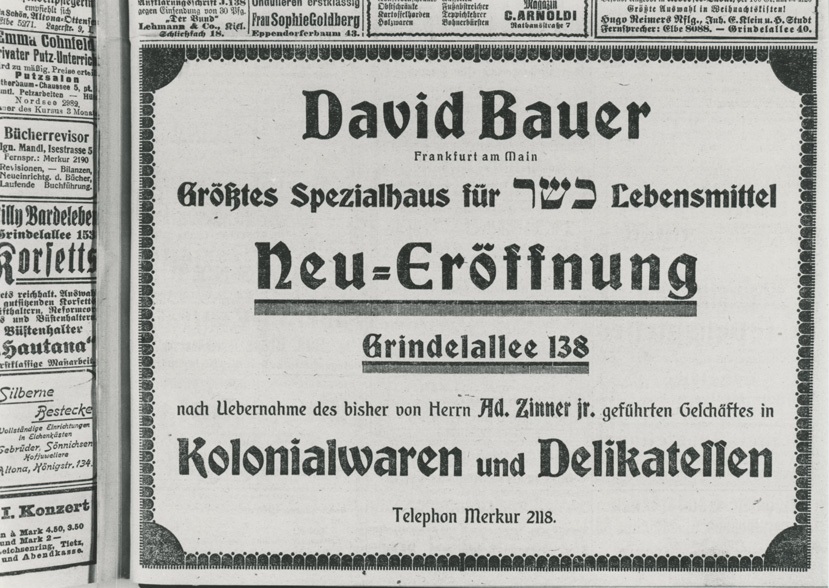

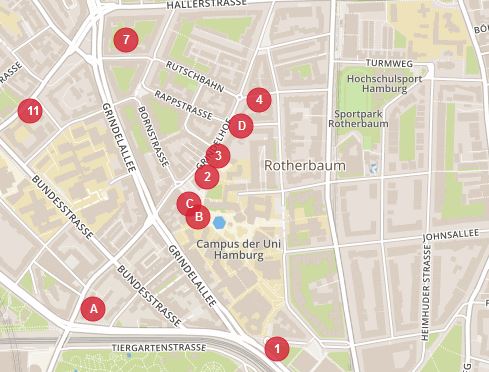

At the end of the 19th century there were about 14,000 Jews living in Hamburg, roughly four percent of Hamburg’s 350,000 inhabitants. Members of the Portuguese-Jewish community only made up a minor share of the city’s Jewish population by now. Until the 1870s three quarters of the Jewish minority had lived clustered around a few streets in the Altstadt [Old Town] and Neustadt [New Town] districts. The founding of the Kaiserreich in 1871 coincided with a migration movement within the city: wealthier Jewish city dwellers now moved to the districts of Rotherbaum, Harvestehude, and Eppendorf. Today’s Grindel quarter in front of Dammtor became the location of the so-called “Little Jerusalem” neighborhood with Jewish retailers and small businesses, the synagogue at Bornplatz, and the Talmud Torah school in its center.

Advertisement for the opening of the grocery trade David Bauer, Grindelallee 138 in Hamburg, 18 x 13

cm

Source: Picture Database of the Institute for the History of the

German Jews, BER00004.

This neighborhood was inhabited mainly by lower middle class, less prosperous, and more devout Jews. Around 1900 ca. 40 percent of all Jews living in Hamburg’s urban area had settled in Rotherbaum and Harvestehude. By about 1925 their concentration in these two districts peaked at 70 percent of the roughly 20,000 Jews living in Hamburg. While the share of Jews in the overall population was only 1.72 percent, it was remarkably high in Rotherbaum and Harvestehude at about 15 percent in each district.

Until 1910 the number of Hamburg’s Jewish inhabitants increased, but their relative share in the population noticeably declined because the city’s overall population grew significantly. Hamburg was still home to the fourth largest Jewish community in Imperial Germany after Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, and Wrocław, yet its almost 19,000 Jews only represented 1.87 percent of the city’s population. In part this was due to the fact that a large share of Hamburg’s Jews belonged to the middle and upper class where the marital age tended to be higher and marriages produced fewer children than was the case among the general population. Only half of all Jews living in Hamburg at this time had been born there. The number of Jews living in Hamburg reached its peak in 1925 when it rose to 19,904.

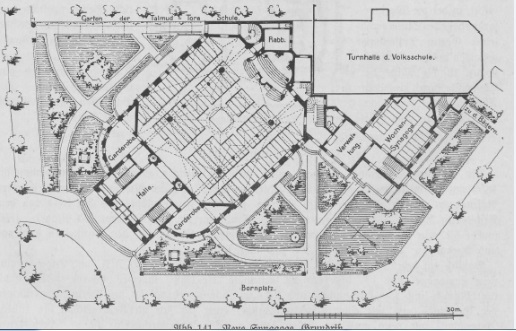

School, gym and synagogue in the Grindel neighborhood

in Hamburg

Source: published in: Hamburg und seine Bauten

unter Berücksichtigung der Nachbarstädte Altona und Wandsbek 1914, ed. by

Architekten- und Ingenieur-Verein zu Hamburg, Hamburg 1914, p. 142, image

141; State- and University

Library Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky, persistent URL: PPN639579191, CC BY-SA

4.0.

Since the turn of the century the Jewish share in the overall population was in nationwide decline, and the absolute number of Jews had also begun to decrease since the mid-1920s. In 1933 they only accounted for 0.77 percent of the total population. This population decline was mainly caused by a drop in birth rates setting in at the end of the 19th century. Meanwhile conversions and individuals giving up their Jewish faith only played a minor role, even though the threatening scenario of loss they evoked loomed disproportionately large.

Some reasons for the changes in the Jewish population’s demographic profile were specific to the Jewish community. The mortality rate among Jews was much lower than among non-Jews, and the life expectancy among newborns was higher than in the overall population, for example. Since the birth rate among Jews declined earlier than it did among Christians and the overall population also benefitted from a declining mortality rate, the share of Jews in the overall population decreased statistically, however.

The marital age among the Jewish population had risen in the course of the 19th century while the number of children per family decreased. These factors contributed to the ageing of the Jewish population. In Prussia the average age for Jews in 1925 was 30.5 years. In 1923, women had an average of 1.3 children. Roughly a quarter of married Jewish women did not have children. Worried contemporaries described this demographic development as “the demise of German Jewry.”

One peculiar aspect of Jewish life was the question how to deal with marriages between Jews and non-Jews. There was a noticeable rise in “mixed marriages” „Mischehen“, meaning marriages across confessional boundaries. These mainly occurred in major cities where the number of the Jewish population was higher after all. Moreover, this was where Jews and non-Jews met in an acculturated urban milieu where religious affiliation had increasingly become a matter of secondary importance. Since 1849 Jews who had acquired citizenship in Hamburg were permitted to marry a member of a different confession. Women were not granted this right until 1851, when civil marriage [Zivilehe] was introduced. In the mid-19th century there also were a growing number of marriages between Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews. The overall number of “mixed marriages” in Hamburg increased significantly and was higher than average; after the First World War they accounted for 25 percent of all marriages involving a Jewish partner, and in 1933 it was almost 60 percent. Numbers like these caused concern within in the Jewish community fearing for its survival because the children of these marriages usually were baptized or at least raised as Christians. The above-mentioned specifics of the Jewish population profile lead to an almost obsessive occupation with demographics among representatives of the Jewish minority. Precisely because they were a minority, threatened by antisemitism from the outside and challenged by the dreaded trend towards dissolution on the inside, the study of the social and demographic development of one’s own social group became central at the turn of the 20th century.

Number of congregation members in Hamburg (including

Altona

and Wandsbek), development between 1815-2004

Source: created by

Fianna Meyer-Sand, based on:

Klaus-Dieter Alicke, Lexikon der jüdischen Gemeinden im deutschen

Sprachraum, München 2008, pp. 1711-1726, here: p. 1712; Arno Herzig (ed.),

Die Juden in Hamburg 1590 bis 1990. Wissenschaftliche Beiträge der

Universität Hamburg zur Ausstellung „Vierhundert Jahre Juden in Hamburg“,

Hamburg 1991.

The rise of National Socialism fundamentally altered the Jews’ socio-demographic profile. Antisemitic repression forced countless Jews to emigrate. The remaining Portuguese families emigrated from Hamburg to the Netherlands, the United States, and to France while only few of them chose Palestine or Portugal as their new home. Between 1933 and the beginning of the Second World War the Jewish population decreased nationwide by roughly 250,000 people due to emigration. This meant the Jewish minority had been reduced by more than half in the course of six years. In Hamburg the number of Jews had decreased from almost 20,000 to 16,885 in 1933.

Pupils of the technical college for tailors in Johnsallee, Hamburg, March 1937, 7 x 5 cm

Source: Picture Database of the Institute for the History of the

German Jews, 21-015/550, collection Ursula Randt.

When the Nuremberg Laws came into effect, the criteria according to which German Jews were counted changed. According to the new racial criteria, not only the 500,000 Jews who were members of a Jewish congregation were counted, but also those who did not belong to any congregation, who were baptized or not religious at all. Those of “mixed-bloods” [„Mischlinge“] were treated as a separate group, and “interracial marriages” were now prohibited. Existing “interracial marriages” remained valid, however. At the end of the war in 1945 there were about 12,000 of these marriages in Germany, 631 of them in Hamburg.

Another cause of this demographic shift were the nationwide forced deportations of Polish or formerly Polish Jews to Poland in late October 1938. In Hamburg this affected about 1,000 individuals. Between 1933 and 1941 a total of ca. 10,000-12,000 Jews emigrated from Hamburg; in 1938 their number was almost as high as in the previous five years combined. The majority of emigrants from Hamburg managed to escape to the United States; Great Britain, Palestine, and China (Shanghai) were other countries chosen by many. Among these refugees were ca. 1,000 children from Hamburg who were taken to Great Britain by the so-called Kindertransporte. On October 23, 1941 emigration was prohibited nationwide. At this point, the number of Jews in Hamburg as defined by the Nuremberg Laws was only 4,951 as a result of the deportations that had already begun. 1,290 of them lived in so-called “interracial marriages.” 85 percent of Hamburg’s Jews were older than 40, and 55 percent were above the age of 60.

At the end of the war there were about 15,000 German Jews on German territory, several thousand of whom had survived in hiding. Most of them had managed to survive because they lived in a so-called “privileged mixed marriage” [„privilegierte Mischehe“] (if the wife was Jewish or if the children were raised as Christians), which protected them from deportation in most cases. About 9,000 Jews who had survived ghettos and imprisonment in a concentration camp outside Germany or in the German-occupied territories such as Theresienstadt returned as well. In addition, there were Jewish Displaced Persons (DP) from eastern Europe, whose number was 53,000 in September 1945. The number of Jewish DPs on German territory grew further, and they came to constitute the largest Jewish group on German territory after the end of the Second World War, concentrated mostly in American-occupied Bavaria. In northern Germany, Bergen-Belsen was the largest center. For most of these DPs Germany was no more than a transit stop. Yet not all of them actually immigrated to the state of Israel founded in 1948 or to the United States. Many remained in Germany, where they founded the first new Jewish congregations. However, the wish to emigrate often continued to persist for a long time.

Most Jews living in postwar Germany were not the descendants of German Jews, but they came from eastern Europe. They had either survived concentration camps or outlived the war in the East and South of the Soviet Union and moved westward after the end of the war. In Germany they ended up in Displaced Persons camps. There also were some German Jews who had emigrated and returned either to the Federal Republic (FRG) or the German Democratic Republic (GDR). They and the Jews from Poland and the Soviet Union formed the base of Jewish congregations in postwar Germany, which were characterized by an ageing membership. In the postwar period the number of (West) German Jews was about 30,000. In the Soviet Occupation Zone about 4,500 Jews were counted; following repression in the early 1950s, only 1,700 Jews in the GDR were registered members of a local congregation. In the 1960s only 10 percent of Jews living in Germany lived in the GDR. While the number of East German Jews decreased due to their high average age, the number of West German Jews remained relatively stable at 25,000-30,000.

In Hamburg there were 647 Jews after the end of the war in 1945, almost all of them part of a “mixed marriage.” A further 50 or 80 individuals had survived persecution and war in hiding or by assuming a false identity. In September 1945 a Jewish congregation in the form of a moderately Orthodox Unified congregation was founded during an assembly in Hamburg attended by nearly 80 people. By March 1947 it had grown to 1,268 members, 671 of whom were married to non-Jewish spouses in so-called “mixed marriages.” Yet membership dwindled due to an ageing population, low birth rates, and emigration.

After the end of the war and into the mid-1950s emigrants continued to return to Hamburg, and eastern European Jews immigrated. Moreover, 150 Jewish families from Iran settled in Hamburg. In subsequent decades the number of congregation members stabilized at around 1,400.

The occupational profile of the Jewish community forming after the end of the Second World War no longer adhered to prewar patterns either. Western Allied policy in the immediate postwar period facilitated the emergence of a particular economic profile in some regions. This was particularly true for the first postwar generation among the Jewish community: the Allies were making licenses for restaurants or bars readily available to Jews living in Germany, many of whom were Polish, and some of them were able to establish themselves in the real estate business. In the retail sector, a concentration of Jewish businesspeople in the textile industry was noticeable in the 1950s and 60s. Another significant group among Jews who had remained in Germany, and even more so among those who had returned to the country, were lawyers: knowledge of both the German language and the country’s legal system proved advantageous for their return to Germany.

Germany’s Jewish community experienced another boost after the fall of the Wall and the reunification of the two German states in 1990, when substantial immigration from the former Soviet Union set in. In the spring of 1990, the GDR government had decided to grant persecuted Jews from the Soviet Union a general right of residence. During the negotiations on the reunification of the two German states, it was decided to retain this immigration policy. As a result of the ensuing immigration, Germany’s Jewish communities changed fundamentally: between 1991 and 2004 about 190,000 of these “quota refugees” migrated to Germany. Nearly half of them joined a Jewish congregation. In 1989, one third of the roughly 1,300 congregation members registered in Hamburg were older than 60. In the following years membership increased and became younger due to immigration. About 30 of the first of these so-called “quota refugees” arrived in Hamburg in 1991 and were cared for by the congregation. By 2004 the congregation already counted 5,000 members.

Detail of the map „Places of Jewish Life in the Grindel“

Source: Places of Jewish

Life in the Grindel, ed. by Cultural Authority

Hamburg in cooperation with Institute for the History of the

German Jews.

As a consequence, Jewish social life changed significantly: a Jewish daycare and the Joseph Carlebach School were founded; the latter has been housed in the building of the former Talmud Torah School since 2002. According to contemporary estimates there are about 200,000 Jews living in Germany today, only half of whom (ca. 108,000 in 2007) are members of a Jewish congregation. In 2015 Hamburg’s Orthodox Jewish congregation counted 2,445 members. A Liberal congregation currently counting about 500 members has existed since 2004.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the work is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Miriam Rürup (Thematic Focus: Demographics and Social Structure), Prof. Dr., is director of the Moses Mendelssohn Zentrum für europäisch-jüdische Studien in Potsdam. Her research deals with gender history, German-Jewish history, contemporary history, history of migration, history of students and universities, history of the politics of commemoration and the history of National Socialism.

Miriam Rürup, Demographics and Social Structure (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-224.en.v1> [April 26, 2024].