The urban region of Hamburg represents a special case in the modern religious

history of German Jewry in several regards: first, because the Ashkenazi Jews of the towns of

Altona,

Hamburg, and

Wandsbek

were organized in the so-called “triple congregation” Dreigemeinde AHW until 1812, and second because both Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews had settled in Hamburg and Altona since the turn

of the 16th to the 17th century yet both groups

continued to practice their faith in separate institutions. Moreover, Hamburg was the first

place in the German speaking realm where Reform Judaism was able to take hold

during the time of the Jews’ integration into the bourgeoisie and emancipation. Going

against the resistance of the traditional majority within its congregation, the

Temple Association

founded in 1817 sought to modernize religious worship

in particular. Several editions of its prayer book also served other Jewish

congregations in Germany, Europe, and the United States as a

model for a reform of liturgical practice.

Hamburg’s Jewish

religious spectrum had been broadened by the founding of the moderately

conservative congregation of the synagogue at Neues

Dammtor Neue Dammtor Synagoge in 1894, although religion and

religious devotion overall became less important in the 19th century. However, only a small number of

Hamburg’s

Jews left the congregation or converted to Christianity. Yet many members of the

Jewish community who still maintained their Jewish faith were no longer willing

to let it take up a significant part of their daily lives. While the National

Socialist regime caused many Jews to return to their religious culture, the

expulsion and murder of Jews also resulted in the complete destruction of their

places of worship. In the aftermath of the Shoah, the newly founded religious

congregations initially were unable to revive the diversity of religious

traditions which had existed before 1933. It was only

in the recent past that new Jewish institutions of various orientations were

established which again express the plurality of religious as well as

non-religious identities.

Numerous authors in various academic disciplines have attempted a definition of the term “Judaism.” The simple criterion which posits that those persons are considered Jews who confess to the Jewish faith and practice it does not apply in all cases. Beginning in the Modern Age in particular, many Jews turned away from religion without denying their Jewish identity, which they understood as based on their ethnic, national, historic or cultural affiliation. In traditional Jewish society, religion had served as an important shared framework indispensable for creating meaning and social cohesion within the community.

Contrary to widespread ideas, various different viewpoints on questions regarding the religious interpretation of the world circulated already in premodern times. Neither did the Jews of the Hamburg-Altona region form a monolithic unit in matters of faith at any time. The conversos hailing from the Iberian Peninsula, also called Marranos, who first settled in Hamburg and Altona around 1600, initially lived as Catholics but later reconverted to Judaism with the support of rabbis, cantors, and teachers from northern Africa and Italy. They were organized in their own congregations observing the liturgical tradition of Sephardic Judaism. Meanwhile, Ashkenazi Jews also founded their own congregations which observed central European rites during prayer services. In 1671, the Ashkenazim of Hamburg, Altona, and Wandsbek united to form the so-called “triple congregation” Dreigemeinde AHW. Until its politically forced dissolution in 1812, it was under the supervision of one rabbi, who resided in Altona and as highest religious authority also judged on matters of family and private law.

Ever since Jews had begun settling in Hamburg, the city’s Lutheran clerics demanded measures be taken in order to convert the Jews. The Edzardian Institution for Proselytizing Jews Edzardische Jüdische Proselytenanstalt existed since 1667 and did indeed manage to convert a number of Jews to the Christian faith. The large majority of both Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews remained loyal to their faith, however. They practiced variations of a normative Judaism, which was rattled when news about the self-styled messiah Sabbatai Zwi reached the “triple congregation” Dreigemeinde AHW; hopes for salvation from exile turned into great despair following his conversion to Islam, however.

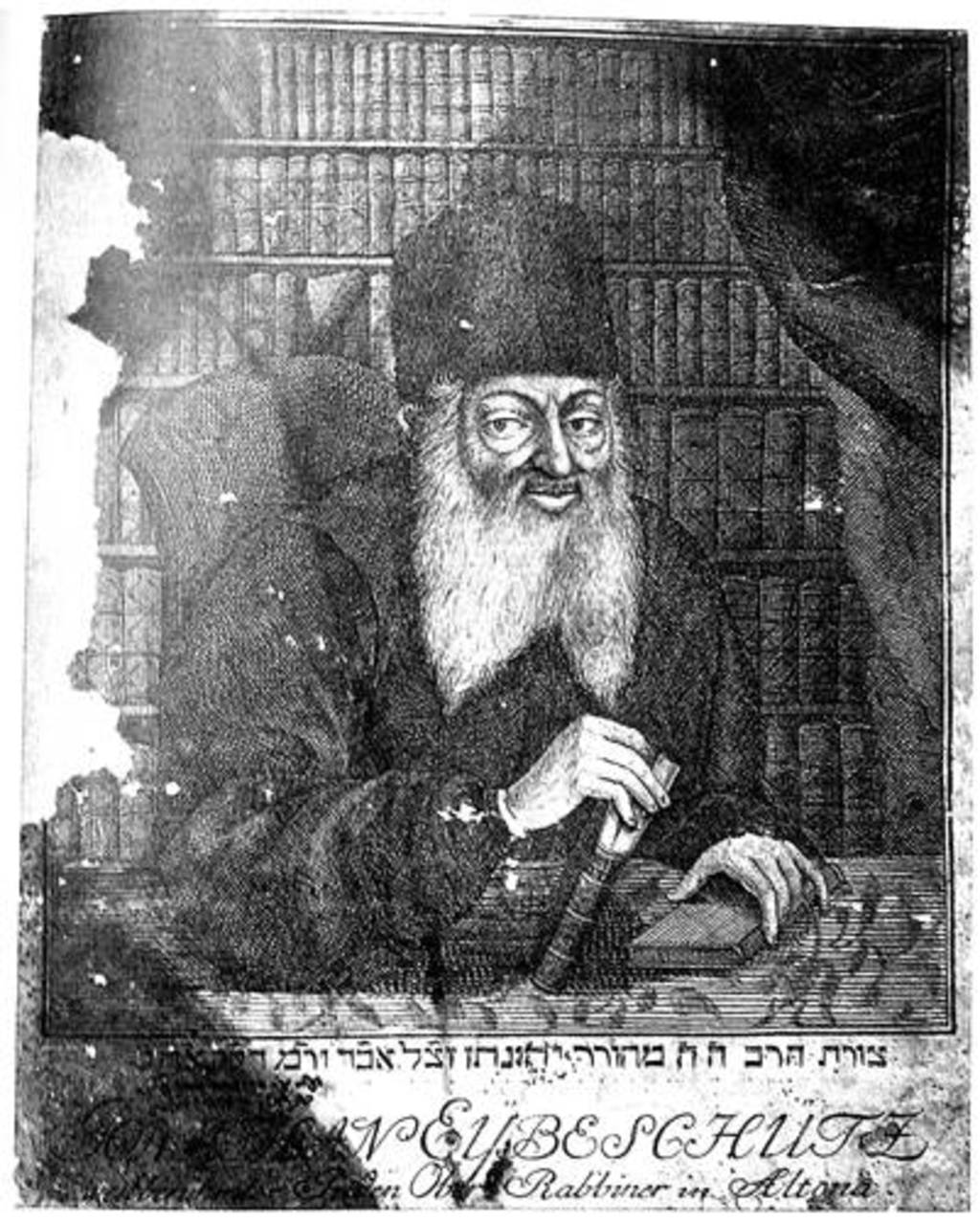

While the basic binding power of Jewish religion as a system of norms and values shaping daily life did not come into question in the following years, the level of religious education slowly began deteriorating in the 19th century. At the same time, the personal observance of religious laws grew less rigorous in many places. The so-called Hamburg amulet controversy [Hamburger Amulettenstreit] unfolding around 1750 in which Jakob Emden, a scholar and printer from Altona, accused the “triple congregation” Dreigemeinde AHW Chief Rabbi, Jonathan Eibeschütz, of being a heretic and a secret follower of Sabbatai Zwi, had a ripple effect all over Europe. This controversy is considered a watershed moment in Jewish historiography since the weakening of rabbinical authority resulting from it facilitated the influx of new ideas into Jewish society.

Posthumous copperplate print of Jonathan Eibeschütz, end

of 18th century.

Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain, originally from: Austrian National

Library, Picture

archive and graph collection, Inventory-No. PORT_00137700_01.

When the ideas of German Enlightenment had also begun to take hold among a small Jewish intellectual elite in the second half of the 18th century, a secular Jewish sphere emerged whose limits constantly expanded. The Jewish Enlightenment, or Haskalah, was an educational project which also gave voice to a general criticism of traditions. The modernization of religious rites did not occur until the 19th century, when German Jews began to seek bourgeois forms of expression for their faith, however. Hamburg was at the vanguard in this search, for it became the place were religious reform found its first institutional foothold. In 1817, Jewish members of the upper middle class signed the founding charter of the Temple Association, which was constituted as a private association existing alongside the congregation.

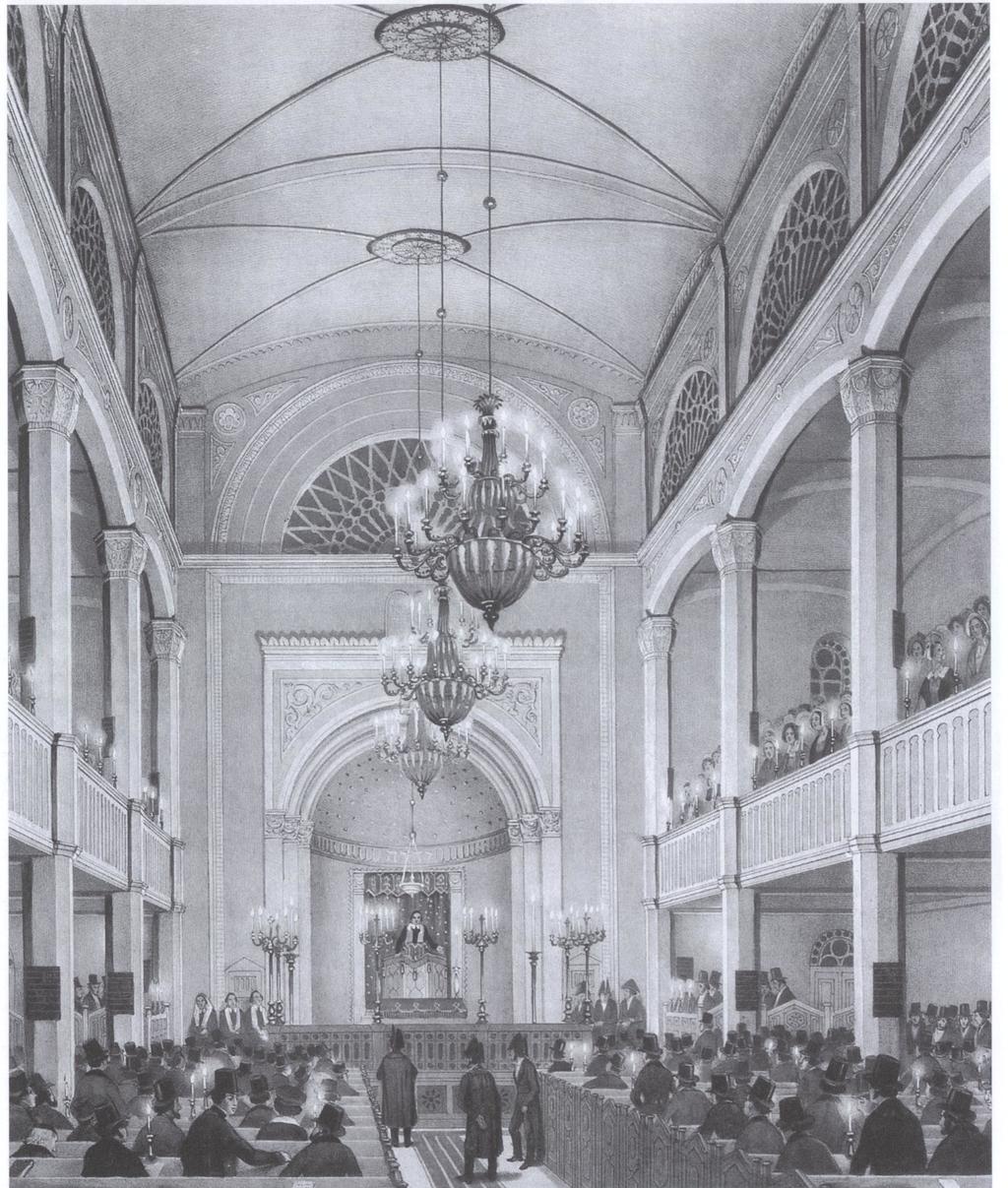

Opening of the New Israelite

Temple in Poolstraße on September 5,

1844.

Source: Picture Database of the Institute for the History of the

German Jews, BAU00281, author: Heinrich Jessen. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

The prayer service the temple established a few months after its foundation adopted significant reforms reflecting both contemporary aesthetic standards and an identification with German culture and national belonging without denying Jewish individuality, however: traditional Hebrew prayers had been shortened and their wording changed, others were omitted entirely, replaced by German hymns or only appeared in German translation or paraphrase. Hopes for the future tied to the Holy Land which by now seemed questionable—awaiting the arrival of the Messiah, the salvation of the Jews by their return to Eretz Israel, the resurrection of the dead and the reintroduction of religious sacrifice—had been weakened or removed altogether. The temple paid much attention to its new musical traditions: while the traditional Jewish prayer service knew neither the singing of hymns nor the instalment of choirs, the temple considered singing in German a fundamental condition for improving religious rites. Sephardic melodies and Sephardic pronunciation, which had previously been unknown in Ashkenazi synagogues, were also considered significant improvements. Much consideration went into other newly introduced elements as well. A boys’ choir accompanied the organ—an instrument which was unknown in orthodox synagogues and would remain so. Services were not led by a traditional rabbi, but by two preachers giving sermons in German on the Shabbat. It was at the temple that the modern edifying sermon first developed into a permanent Jewish institution. By these changes as well as by its very name, the temple distanced itself from other synagogues in and around Hamburg.

Cover of the General Israelite Songbook. Introduced in the New Israelite Temple of

Hamburg

Titelblatt des Allgemeinen Israelitischen Gesangbuch. Eingeführt in dem

Neuen Israelitischen

Tempel zu Hamburg, 1833.

Source: archive.org, public domain.

Developments in Hamburg illustrate that even Jewish orthodoxy did not react with rigidity or inflexibility to the challenges of modern bourgeois society either, but instead also reinvented itself as a bourgeois confession. Isaak Bernays, who was elected to the office of Chief Rabbi of Hamburg’s Jewish congregation in 1821, was not a traditional scholar in that he not only had a deep knowledge of his religion but also an eclectic general education, which he demonstrated in his German-language sermons. Bernays documented the shift in the way he understood his office by not calling himself rabbi but instead using the Sephardic title chacham. Nevertheless, Bernays remained a passionate opponent of the temple all his life.

Since the 1830s in particular, religious reform began to take hold in other German synagogues as well. Around 1850 the religious spectrum was composed of various orthodox and reformed orientations: while the “old orthodoxy” quickly became less significant due to its skepticism towards emancipation and assimilation, a “neo-orthodoxy” emerged which combined loyalty to religious laws with an embrace of European culture. On the other side of the spectrum, there were several variations of Reform Judaism, some more radical, some less. Moreover, a moderately conservative movement positioned itself between the reformed and the orthodox, combining the belief in a revelatory core of Judaism with an acknowledgement of the historical development of tradition.

Despite this diversity of modern religious interpretations of the world, it is safe to assume that a majority of the Jewish population, while not completely unaffected by these changes, adhered relatively strictly to the religious traditions and practices of previous centuries until the mid-19th century. The rhythm of Jewish life continued to differ from its non-Jewish environment insofar as Jewish dietary laws and the Jewish calendar as well as holidays and days of rest represented religious, cultural, and social barriers. Strict observation of the prohibition of work on the Shabbat continued, and especially outside of the urban areas the pressure to conform was so strong within synagogue congregations that a lively, culturally prescribed religiosity continued to exist.

In Imperial Germany, Reform Judaism, now called “liberal Judaism,” presented itself as a largely accepted phenomenon of Jewish reality. In many places orthodoxy lost its significance because it lost control over its local religious institutions. In Prussia, where the majority of German Jews lived, the so-called Parochialzwang, a law which bound Jews to one particular congregation based on where they lived, was not repealed until a law allowing them to leave and change congregations Austrittsgesetz was passed. With the passing of the law in 1876, “every Jew was permitted to leave the Jewish congregation he belonged to by law, legal custom or an administrative regulation out of religious concerns." In Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, and other cities, orthodox splinter congregations formed, having split off from the major congregations. Neither Altona nor Hamburg saw such splits. Reform Judaism never managed to gain a foothold in Prussian Altona’s High-German Israelite Congregation Hochdeutsche Israeliten-Gemeinde. The influx of eastern European Jews since the 1880ies most likely reinforced the congregation’s conservative profile. Meanwhile, in the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, the so-called Hamburg system was established by an 1867 statute issued by the German-Israelite Congregation Deutsch-Israelitische Gemeinde (DIG) after mandatory membership in a congregation had been repealed there. Responsibility for religious services was now given to the two religious associations by the DIG, which functioned as an umbrella organization. The liberal temple association largely enjoyed the same rights as the orthodox synagogue association, which represented the interests of those Hamburg Jews strictly observing religious laws. The Synagogue at Neues Dammtor Neue Dammtor synagogue founded in 1894, which practiced moderately conservative rites and thus positioned itself between orthodoxy and the Temple, was recognized as a third religious association in 1923.

Entrance of the Temple Oberstraße.

Source: Institute for the History of the

German Jews, photo: Paula

Oppermann, 2013.

Overall, religion continued to lose its significance and increasingly lost its place in daily life. Jewish congregations, which had originally defined themselves as faith-based communities, sought to compensate for this by increasing the amount of cultural activities they offered. The question whether it is justified to speak of a true renaissance of Jewish culture during the Weimar Republic remains controversial. In the period of National Socialism, cultural associations also offered religious refuge to their members suffering from increasingly severe discrimination and ostracism as “non-Aryans.” Yet religious life, too, was targeted by the Nazi party and its authorities. In April 1933, a new “Law on the Butchering of Animals” penalized the killing of livestock without prior stunning. Jewish dietary law does not allow the stunning of animals before slaughter. It stipulates that only meat from animals butchered by the method of shechita, a quick cut to the throat, is kosher and may be consumed. When the new law was passed, orthodox Jews therefore found themselves faced with a dilemma which could not be solved satisfactorily even by resorting to costly imports of meats from abroad. The removal of the Jewish Grindel cemetery in 1937, in the course of which remains had to be exhumed and reburied at the Jewish section of the Ohlsdorf cemetery, represented an act of persecution targeted at the Jewish faith as well.

Following the passing of the Greater Hamburg Law [Groß-Hamburg-Gesetz] in 1937, which stipulated the incorporation of Prussian towns and rural districts surrounding the city, the previously independent synagogue congregations of Wandsbek and Harburg-Wilhelmsburg were dissolved altogether while the High-German Israelite Congregation Hochdeutsche Israeliten-Gemeinde Altona managed to retain a certain amount of independence as the fourth religious association under the umbrella of Hamburg’s German-Israelite Congregation. In the aftermath of the November pogrom, most of the synagogues in Hamburg and Altona were no longer available to their congregations for prayer services. They had been vandalized, set on fire or closed. Until his deportation in December 1941, Chief Rabbi Joseph Carlebach led services at the synagogue on Beneckestraße where all orthodox services took place since its reopening in February 1939. Liberal Jewish cleric Joseph Norden organized services at the former Lodge quarters on Hartungstraße until he, too, was deported in July 1942. By 1943 services were no longer held in the Hamburg area. At best, the Jewish faith could only be practiced privately.

Building of the synagogue at Hohe Weide.

Source: Institut für die

Geschichte der deutschen Juden, photo: Ute Schumacher, 2017.

In 1945, after World War II had ended, a Jewish congregation was newly founded by a small number of Hamburg Jews. Most of them had survived the years of National Socialist rule because of their marriage to a non-Jewish spouse, which had afforded them a certain amount of protection. Hamburg’s Jewish congregation conceived itself as a uniform congregation which had no need for ritual associations and instead decided on a moderately orthodox structure in both its liturgy and its religious institutions. The new congregation’s establishment culminated in the opening of a new synagogue at Hohe Weide in 1960. However, a true revival of both liberal and conservative tradition was not able to take place for many decades. It is only in the recent past and not least due to the influence of migration from the countries of the former Soviet Union that the beginnings of a more diverse approach towards living one’s faith have been emerging. The establishment of an egalitarian prayer circle, the Liberal Jewish congregation founded in 2004, the conservative Masorti congregation of Kehilat Beit Shira existing since 2009, as well as the center run by the international ultraorthodox group Chabad Lubawitsch all testify to the desire to again establish different religious positions in Hamburg in the hope that they will endure.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the work is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Andreas Brämer (Thematic Focus: Religion and Identity), PD Dr. phil., Deputy Director of the IGdJ, is a member of the board of the Wissenschaftliche Arbeitsgemeinschaft (Academic Working Group) of the Leo Baeck Institute. His research foci include German-Jewish history of the 19th and 20th century, Jewish history "from the inside", Jewish religious history and the history of Jewish historiography.

Andreas Brämer, Religion and Identity (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-216.en.v1> [April 27, 2024].